In the 34th in a series of posts on 2012 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, Ray Morrison, author of In a World of Small Truths (Press 53), reveals the wellspring of his work.

Inspiration comes at the moment when the world outside me becomes the world inside me. Often it starts from an innocuous moment—the call from an old friend with the unexpected news of divorce, reading a newspaper article about a love triangle that ends in murder, a close friend’s tale of surgery and its aftermath. These commonplace things propel words onto the page for me, for I crave a real-world connection in my stories. A link to the small, unique worlds in which each of us exist. And within each of our private worlds exist a multitude of truths, some small and some large, to which we all are anchored. But many of these truths we hold onto are flawed beyond our own ability to detect, and so we find ourselves on occasion treading in complicated and uncomfortable places. It is those moments—and how we respond, good or bad—that holds my interest and animates the characters in my stories.

The beauty of finding inspiration from ordinary life is never knowing when I’ll encounter my next story. Will it be at a baseball game? The homeless man soliciting alms on the corner while I idle at the intersection? Will it be my daughter’s innocent comment in the backseat of our car? The sight of a fish bowl on my kitchen counter? These have all served as germs that have grown into stories found within In a World of Small Truths. A writer, it seems to me, is the observer and translator of the world around us. I am, if you will, the register of human deeds.

|

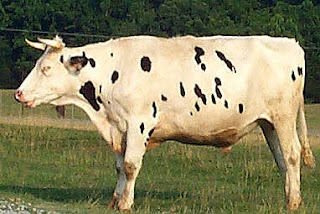

| The horns of a dilemma |

Yet the challenge I set for myself is to present the “ordinary” in a way that is in equal parts meaningful, entertaining and personal for my readers. First loves are universal, but can border on mundane to those not involved in them unless, perhaps, we add an ornery Holstein bull in the mix. A teenager’s high school history report is a drab basis for drama until we have her fall head-over-heels in love with a dead president. A spat with a neighbor over excessive holiday decorations that is peacefully resolved is far less entertaining than if it turns accidentally violent. Therein lies the joy I find in writing short stories: finding the right costume to dress up the unremarkable.

In a World of Small Truths, as a collection, is my effort at doing just that. To take my imaginary people and make them seem as real as the readers who meet them. I don’t set out to try to leave my readers with a moral or a “message.” Nor do I try to (for I cannot) create fantastical worlds to which readers can escape. Rather, I merely attempt to guide them across the very world we all share. I consider myself successful if one person comes away after reading any of my stories thinking of how sad, yet how true; how wonderful, but so true; how surprising, however so very true. We are, all of us, immersed in large and accepted truths, but it is the personal ones, the small truths, that connect us as individuals, one to another.

This is the world of my stories.