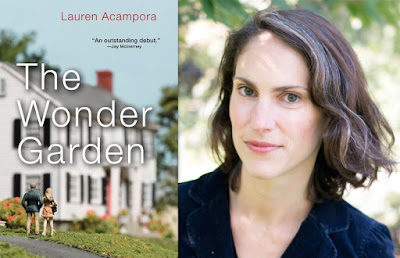

In the sixth in a series of posts on 2015 books entered for The Story Prize, Lauren Acampora, author of The Wonder Garden (Grove Press) takes us through her creative process.

9:05 a.m.

Arrive five minutes late to daughter's preschool. Brush her hair in parking lot, walk her to classroom, taking time to hop on big orange polka dots on floor.

9:15 a.m.

Back to car, sneaking out side exit to avoid running into friends and chatting too long.

9:22 a.m.

Arrive at magical hidden courtyard with antique store, chiropractor, and yoga/wellness center. Park dirty Subaru between two Range Rovers, haul out laptop bag, trudge through snow to raw food café. Café empty, as usual; whale sounds on New Age radio station. Settle into special corner table near potted jade plant. Fix cup of tea, because the cold-pressed live-enzyme juices cost ten dollars. Let tea steep on windowsill while booting up computer.

9:30 a.m.

Go to bathroom, recoil at image in mirror, hair disheveled and still wet from shower.

9:35 a.m.

Back at table. Check email, reply to messages about play dates. Wish someone happy birthday on Facebook. Check local news for emergencies requiring immediate rescue of daughter.

9:45 a.m.

Look at The New York Times online. Any emergencies? Get sidetracked by opinion piece about some political outrage.

9:50 a.m.

Write email to congressman/senator.

10:00 a.m.

How did it get to be 10:00?!? Close browser, turn off WiFi, open Word doc. Read through story-in-progress, reach part that's terrible. Revise until less terrible. Add new paragraph.

10:15 a.m. Get stuck on particular word—just on tip of tongue. Turn WiFi back on to use Thesaurus.com. Dig up fabulously perfect synonym. Surreptitiously check email.

10:30 a.m.

Take first sip of tea, already cold. Refill with hot water. Go to bathroom again, passing woman at cash register. Feel guilty for only buying tea and using bathroom so much. In bathroom, think about everything wrong with story-in-progress and whisper swear words at self in mirror.

10:45 a.m.

Hit stride on new paragraph; write another and another. Forget about tea and whale sounds.

11:45 a.m.

Yoga classes end. Ladies come into café, healthy and perspiring, and order the ten-dollar juices, glancing at my corner table. Realize I am still wearing my parka and look like Ally Sheedy in The Breakfast Club.

11:55 a.m.

Yoga ladies leave; guy at café counter gives me cup of leftover kale juice from blender. For free!

12:00 noon

Just about to nail complicated, profound sentence; just getting into rhythm of new paragraph; time to close laptop. Zip up laptop bag, zip parka, throw out tea cup, give two dollars to woman at cash register. Try not to slip on ice while running to parking lot.

12:15 p.m.

Arrive back at preschool. Buckle daughter into car seat, deliver emergency snack bag of pretzels, put on Pete Seeger CD. Drive home singing "Guantanamera."

Take first sip of tea, already cold. Refill with hot water. Go to bathroom again, passing woman at cash register. Feel guilty for only buying tea and using bathroom so much. In bathroom, think about everything wrong with story-in-progress and whisper swear words at self in mirror.

10:45 a.m.

Hit stride on new paragraph; write another and another. Forget about tea and whale sounds.

11:45 a.m.

Yoga classes end. Ladies come into café, healthy and perspiring, and order the ten-dollar juices, glancing at my corner table. Realize I am still wearing my parka and look like Ally Sheedy in The Breakfast Club.

|

| Sheedy: Basket case |

11:55 a.m.

Yoga ladies leave; guy at café counter gives me cup of leftover kale juice from blender. For free!

12:00 noon

Just about to nail complicated, profound sentence; just getting into rhythm of new paragraph; time to close laptop. Zip up laptop bag, zip parka, throw out tea cup, give two dollars to woman at cash register. Try not to slip on ice while running to parking lot.

12:15 p.m.

Arrive back at preschool. Buckle daughter into car seat, deliver emergency snack bag of pretzels, put on Pete Seeger CD. Drive home singing "Guantanamera."