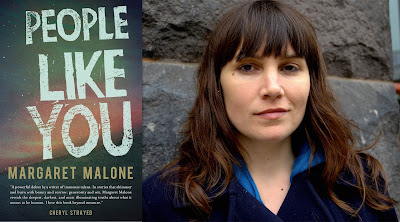

In the 48th in a series of posts on 2015 books entered for The Story Prize, Margaret Malone, author of People Like You (Atelier26), discusses how her starting point for stories has changed from a sentence to an image.

When I first started writing, I exclusively found my ideas for stories in the sudden appearance of a single, complete rhythmic sentence that would pop into my head while I was always in the middle of doing something else. I’d be walking the dog, or taking a shower, or sweeping the kitchen floor when, Bloop!, a little universe of an idea would announce itself. It typically had a person, a place, and a thing all strung together, and the sentence usually carried a particular cadence, almost as if it was a stanza from a poem I’d memorized years before.

The sentence would show up and then I’d mentally chew on it a few times to test it out, make sure it wasn’t all flash and bluster but had some real value, but was the kind of sentence you could dig claws into. If it was, I’d hurry to scribble it down in my notebook. Then, later that day or the next day, when I sat down to write, I’d find the sentence, write it down again at the top of a blank page and let fly: I’d write and write and write and keep writing until I arrived at some kind of a something that felt like it could maybe turn into the kind of thing that just might one day become a story.

I was in my late twenties and fearless: I’d started writing “so late” I wasn’t sure I’d have the time to evolve into a very good writer, so with nothing at stake, most days I’d unleash a wild rush of sentences in my notebook without much care or forethought, and I wouldn’t stop writing until the place I landed felt different than the there where I began.

Years passed. The writing life beat me up a little (as it does), and real life beat me up a lot (as it will), and the sudden appearances of the unasked-for perfect sentence became extinct.

When I first started writing, I exclusively found my ideas for stories in the sudden appearance of a single, complete rhythmic sentence that would pop into my head while I was always in the middle of doing something else. I’d be walking the dog, or taking a shower, or sweeping the kitchen floor when, Bloop!, a little universe of an idea would announce itself. It typically had a person, a place, and a thing all strung together, and the sentence usually carried a particular cadence, almost as if it was a stanza from a poem I’d memorized years before.

The sentence would show up and then I’d mentally chew on it a few times to test it out, make sure it wasn’t all flash and bluster but had some real value, but was the kind of sentence you could dig claws into. If it was, I’d hurry to scribble it down in my notebook. Then, later that day or the next day, when I sat down to write, I’d find the sentence, write it down again at the top of a blank page and let fly: I’d write and write and write and keep writing until I arrived at some kind of a something that felt like it could maybe turn into the kind of thing that just might one day become a story.

I was in my late twenties and fearless: I’d started writing “so late” I wasn’t sure I’d have the time to evolve into a very good writer, so with nothing at stake, most days I’d unleash a wild rush of sentences in my notebook without much care or forethought, and I wouldn’t stop writing until the place I landed felt different than the there where I began.

***

Years passed. The writing life beat me up a little (as it does), and real life beat me up a lot (as it will), and the sudden appearances of the unasked-for perfect sentence became extinct.

I spent a whole bunch of years wondering what I was doing wrong. Why were those beautiful, sad, funny sentences not around anymore? Where did they go? Was someone else receiving them now? Who was this person? What was he or she writing?

Still somehow I had the wherewithal (read: desperation) to keep putting words down onto the page. I wrote stories, and I wrote some essays, and I wrote some more stories. Occasionally something would be published; usually not. And somewhere in there I became aware that, without realizing it, I had started to hurriedly scribble ideas down in my notebook again. But the ideas were not born from a sentence anymore.

Now they were born from an image.

The image was more than that though—it was really a moment in time I’d seen or imagined that was often accompanied by a very particular feeling. The full effect was so complete I’d feel a click go off inside me, like I was taking a picture with a camera, a very special camera that could photograph image and feeling together.

|

| Finding images that click |

This picture would stay with me. I’d carry it around, this feeling picture, in much the same way that I used to mentally carry a sentence around before writing it down in the old days.

Just like I used to chew on those early pop-up sentences, I’d pull up the memory of the picture to see if it still held the same resonance as the moment I saw whatever I saw when the snap and click of the camera went off. If it stayed with me, I’d eventually write the full feeling picture idea down in my notebook.

It is not uncommon now for one of these feeling pictures to be so strong, so haunting, or so odd, I do not need to go looking through my notebook for the reminder of it. The image is with me all the time and I’m just waiting for the moment I can sit down and see what happens when I plant the feeling picture on paper and let it grow sentences—who are the people in this place feeling these things?

I’d like to say I have no preference for how a story gets started, that I’ll take whatever I can get, but it’s not true. I prefer the way it is now. In the early version, the story ideas were born of logic—the crisp cadence of a string of words that I needed to pull along to the place they needed to be. Now, those feeling pictures are like windows to places that already exist, fully thriving with layers of chaos and order. The sentences were nice, but the windows are magic—I climb over the sill and through the panes and land inside a world that creates itself as I explore it. I visit the world and come back to this one with images and feelings to unpack on the page, and I know I am done when the feeling of the written story at last matches that first gut punch of the picture when the camera shutter clicked and the feeling image developed and I knew instinctively discovering the story behind the feeling picture would be worth all the days and weeks and sometimes years to make the moment make sense. So far, it always is.