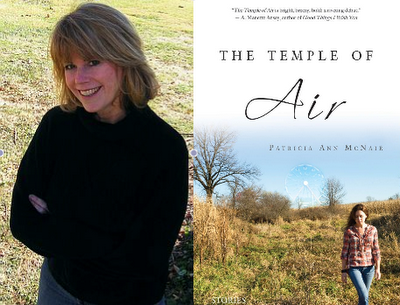

In the 62nd in a series of posts on 2011 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, Patricia McNair, author of The Temple of Air (Elephant Rock), reveals her sources.

I sit with my husband at a restaurant, and across the way near a large, haunting, abstract painting on a brick-face wall, another couple lean in toward one another, then away. The man leaves his hand on the table between them, palm up; the woman pulls her shoulders back and crosses her arms over her chest. She is weeping.

I lived in a house in a small subdivision between two lakes in Iowa, and the wife of the couple next door was badly scarred. A deep caving in of flesh was where bone and muscle should have been, but wasn't. I found out later that her husband shot half of her face off. A hunting accident. They gave up hunting. She stopped eating meat.

On a huge Ferris wheel—one with swinging cages instead of bench seats—I watch as a father lets his little boy, an infant, crawl around the floor of the ride, putting his head against the bars that are supposed to keep us safe.

When I worked on the trading floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, there were twin brothers who—in their forties, perhaps fifties—still dressed alike and lived together. They were each single, never married. One was the nice one. One was not.

In my teens I babysat for a girl with Down's Syndrome. She was younger than me but actually quite a bit larger, heavier. One afternoon while she settled in for a nap, I dozed on a couch in the den. I woke up when the girl was on top of me, hitting me.

Friends tell me stories: There’s a woman with a double mastectomy and a man working in her house; a mother tried to give up eating in order to find enlightenment; a woman suspected her husband of cheating only to find out he was distracted by his serious (and secret) illness. I listen carefully and store it all away, just in case. One writer friend knows what I am up to, and so she prefaces her stories—the really good ones—with: Now, you can’t have this one; this one is mine.

They are all ordinary moments from my ordinary life, really, but ones that stay with me, draw me to them and through them in search of narrative. I gather these instances, never quite sure when they will present themselves to me, unbidden at times, or at others, dragged out from the murky shadows of memory. I sit with my pen and my journal, or my fingers on a keyboard, and scan through those things I have witnessed, I’ve been told, I’ve noted, and I wonder about still—days, years, sometimes decades after this happened, after that occurred.

Here—in each day I make my way through—is where story lives. The couple pulling apart at the table, the scarred wife, the endangered child, the odd twins, the big girl and her babysitter, the man in the house, the longing mother, and the distracted husband each have found a home in my linked collection, The Temple of Air. They are no longer the people I saw or was told about, they are no longer the people I knew. They have become others, characters created, who populate the pages of the stories I’ve imagined in the lives I’ve discovered.

It is this, this moving from watching, gathering, storing away, to writing it down that changes things. What was real, what really happened, no longer matters, at least not to me. It is an interesting tension, this pull between observation and imagination, this balance of seeing it happen and making it happen. This place that is settled somewhere between what is real and what is imagined is where I come to do my work; this is where I live my storied life.