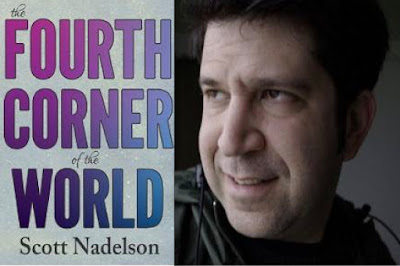

In the third in a series of posts from authors of 2018 books entered for The Story Prize, Scott Nadelson, author of The Fourth Corner of the World (Engine Books), talks about his struggles to write a story he'd been pursuing for a long time and what ended them.

Describe a breakthrough you’ve experienced:

I first read the article in 1999. It came across my desk at the small community newspaper where I edited the calendar of events and wrote occasional arts features. Three pages in an academic journal, describing a radical Jewish utopian colony in the southern Oregon wilderness in the 1880s. It was short on details, but what was there I found fascinating.

The colonists, members of a pre-Zionist emigration organization in Ukraine, promoted an early back-to-the-land movement for young secular Jews, as a way to escape anti-Semitism and pogroms. They named the colony New Odessa. Those who lived there were all in their late teens and early twenties. Lifelong city dwellers, they knew nothing about farming and would have starved the first winter if generous neighbors hadn’t donated food. Afterward they survived by cutting timber, which they sold to the rail company building tracks in the valley below. Among other ways they were ahead of their time, they championed equality between the sexes and free love. The only problem was, there were twice as many single men as women, and love triangles quickly led to strife. The colony dispersed after five years.

What hooked me, above all else, were the many gaps in the historical record. There were only a handful of first-person accounts, most fragmented, and little archival material. The story was wide open, in other words, and it spoke to me personally, as a Jew in my twenties who’d abandoned his ancestral home (suburban New Jersey) for the wilds of Oregon (late-’90s Portland). It was a story of exile, the self-imposed kind, that comes with equal measures of hope and doubt.

But for years I couldn’t write the story. I did all the research, I spent many hours imagining the lives of these young men and women from Odessa, but every time I tried to set words on paper, the narrative evaporated. I could conjure characters, setting, even plot—always my weakest point—but what escaped me was the language to contain it all. I kept trying to negate the voice of the person writing in twenty-first century Oregon, to find inflections that would convince me I was really inhabiting the consciousness of someone who’d lived a hundred years before I was born. Failing, I tried to abandon the material more times than I care to admit.

Then, about sixteen years after first discovering New Odessa, I happened to re-read the opening chapter of David Malouf’s Remembering Babylon. It’s an astonishing novel from start to finish, and its first sentence is a knockout: “One day in the middle of the nineteenth century, when settlement in Queensland had advanced little more than halfway up the coast, three children were playing at the edge of a paddock when they saw something extraordinary.” The opening phrases establish a crucial stance: This is someone speaking in the present, with knowledge and perspective about how things have changed. Malouf makes no attempt to convince you he is writing from the nineteenth century, not yet. He gives us scope, tells us exactly when and where we are, provides a stripped-down image of children playing, but no details. Those will come, he seems to tell us, but for now, just picture these children, a pasture, a place where settlement has just reached. And then he hits us with mystery and promise: “something extraordinary.” The sentence does everything necessary to point us forward. It tells us where we’re viewing from, where we’ll go, and what to look for. It combines the simplicity of folktale with the authority of historical reconstruction.

After reading it a dozen times, I returned to my utopian colony. I mimicked Malouf’s syntax, and almost immediately a path opened in front of me. It was the rhythm that allowed me to enter this story I knew so well, the sound of the language that helped me discover all I had yet to understand. Embodying the characters no longer felt forced because I was doing so as myself, a twenty-first-century writer imagining what it might have felt like to be a young Ukrainian Jew encountering the mysteries of sex and love and death in a wilderness thousands of miles from home. Some sixteen years and three weeks later, I had a draft of what would become the title story of my collection, The Fourth Corner of the World.

According to the great Texas writer William Goyen, story is “the music of what was,” not a record of what happened but a song that makes us feel it. What Malouf’s sentence reminded me is that I can bring the past alive only when I learn how to sing about it.

Describe a breakthrough you’ve experienced:

I first read the article in 1999. It came across my desk at the small community newspaper where I edited the calendar of events and wrote occasional arts features. Three pages in an academic journal, describing a radical Jewish utopian colony in the southern Oregon wilderness in the 1880s. It was short on details, but what was there I found fascinating.

The colonists, members of a pre-Zionist emigration organization in Ukraine, promoted an early back-to-the-land movement for young secular Jews, as a way to escape anti-Semitism and pogroms. They named the colony New Odessa. Those who lived there were all in their late teens and early twenties. Lifelong city dwellers, they knew nothing about farming and would have starved the first winter if generous neighbors hadn’t donated food. Afterward they survived by cutting timber, which they sold to the rail company building tracks in the valley below. Among other ways they were ahead of their time, they championed equality between the sexes and free love. The only problem was, there were twice as many single men as women, and love triangles quickly led to strife. The colony dispersed after five years.

What hooked me, above all else, were the many gaps in the historical record. There were only a handful of first-person accounts, most fragmented, and little archival material. The story was wide open, in other words, and it spoke to me personally, as a Jew in my twenties who’d abandoned his ancestral home (suburban New Jersey) for the wilds of Oregon (late-’90s Portland). It was a story of exile, the self-imposed kind, that comes with equal measures of hope and doubt.

|

| New Odessa colonists |

But for years I couldn’t write the story. I did all the research, I spent many hours imagining the lives of these young men and women from Odessa, but every time I tried to set words on paper, the narrative evaporated. I could conjure characters, setting, even plot—always my weakest point—but what escaped me was the language to contain it all. I kept trying to negate the voice of the person writing in twenty-first century Oregon, to find inflections that would convince me I was really inhabiting the consciousness of someone who’d lived a hundred years before I was born. Failing, I tried to abandon the material more times than I care to admit.

Then, about sixteen years after first discovering New Odessa, I happened to re-read the opening chapter of David Malouf’s Remembering Babylon. It’s an astonishing novel from start to finish, and its first sentence is a knockout: “One day in the middle of the nineteenth century, when settlement in Queensland had advanced little more than halfway up the coast, three children were playing at the edge of a paddock when they saw something extraordinary.” The opening phrases establish a crucial stance: This is someone speaking in the present, with knowledge and perspective about how things have changed. Malouf makes no attempt to convince you he is writing from the nineteenth century, not yet. He gives us scope, tells us exactly when and where we are, provides a stripped-down image of children playing, but no details. Those will come, he seems to tell us, but for now, just picture these children, a pasture, a place where settlement has just reached. And then he hits us with mystery and promise: “something extraordinary.” The sentence does everything necessary to point us forward. It tells us where we’re viewing from, where we’ll go, and what to look for. It combines the simplicity of folktale with the authority of historical reconstruction.

After reading it a dozen times, I returned to my utopian colony. I mimicked Malouf’s syntax, and almost immediately a path opened in front of me. It was the rhythm that allowed me to enter this story I knew so well, the sound of the language that helped me discover all I had yet to understand. Embodying the characters no longer felt forced because I was doing so as myself, a twenty-first-century writer imagining what it might have felt like to be a young Ukrainian Jew encountering the mysteries of sex and love and death in a wilderness thousands of miles from home. Some sixteen years and three weeks later, I had a draft of what would become the title story of my collection, The Fourth Corner of the World.

According to the great Texas writer William Goyen, story is “the music of what was,” not a record of what happened but a song that makes us feel it. What Malouf’s sentence reminded me is that I can bring the past alive only when I learn how to sing about it.