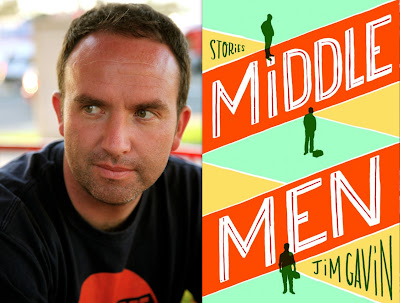

In the first in a series of guest posts by the authors of 2013 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, Jim Gavin, author of Middle Men (Simon & Schuster), reveals his affinity for a lesser-known Flannery O'Connor story.

I was introduced to Flannery O’Connor by a giant rugby player with a shaved head. He was my freshman year RA at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. We never spoke a word to each other, but one day I heard him talking to a friend about a writing class he was in, and how he had spent much of his Christmas break copying out a bunch of Flannery O’Connor stories, word for word. “Why?” his friend asked, faintly horrified, and the rugby player said, “So I can see how she does it.” The friend still looked aghast, and I felt the same way. This seemed like a colossal waste of time, a grim and pointless chore. It would be a long time before I actually knew anything about Flannery O’Connor, or read any of her work, or started to think about myself as a fiction writer, but I never forgot the image of this hulking bald dude, bent over a table, copying out her sentences. What was it about this woman that inspired such monastic devotion?

The summer after I graduated from college I lucked into a job at a newspaper. I worked ghoulish hours on the sports desk, three o’clock until eleven. Wired after the deadline rush, I’d stay up until four or five in the morning, watching ungodly amounts of bad TV, and, occasionally, reading. At some point I picked up The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor – that beautiful FSG edition, with the three peacock feathers symbolizing the undivided substance and co-eternal majesty of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But mainly they’re just blue-green peacock feathers and they look really nice set off against the white background and gold lettering. Late at night, with Sportscenter on mute and a plate of microwaved nachos by my side, I made my way through these stories, in no particular order. I began reading in the kind of solemn mood I thought one had to bring to a Major Work of Literature, especially one written by a woman who had died tragically at the height of her powers, but this fell away once I figured out, fairly quickly, that as a writer, O’Connor was, above all things, fucking hilarious. One story in particular stood out to me: “The Partridge Festival.”

Calhoun, a twenty-three year old air conditioning salesman and aspiring writer, has driven, in his “small pod-shaped car,” to the town of Partridge, where he plans to stay a few nights with his great aunts – “box-jawed old ladies who looked like George Washington with his wooden teeth in.” They think he is there to enjoy the annual Azalea Festival, but really he has come to learn more about the man, Singleton, whose actions had recently put the town’s impending jubilation under threat:

After speaking to a few more people, Calhoun decides that the only way he can do justice to Singleton’s story is by writing a novel. Before he can do this, however, his aunts set him up on a date with a neighbor girl, Mary Elizabeth. Calhoun deigns to go for a walk with her. Looking at her round childish face, he concludes that she is retarded. But then, to his great annoyance, he finds out that she is, in fact, an aspiring intellectual and writer, and that she too hates the town and believes in the innocence and heroism of Singleton. From there they engage in an epic pissing contest, arguing over who understands Singleton more, and who should be allowed to write his story. O’Connor often has a field day with frustrated intellectuals, but Calhoun and Mary Elizabeth stand out as perhaps her most pompous and insufferable creations. Eventually they decide to go visit Singleton at the insane asylum. The brief meeting, which doesn’t go quite how they imagined, is one of the funniest moments in the collected stories, and for a long time it’s what I always remembered most about “The Partridge Festival.”

In my early twenties I took some writing classes, but they didn’t really take, and for a long time I just drifted. After not writing anything for a few years, I decided to sign up for a fiction class at UCLA Extension. At the time I worked in the plumbing industry. I was a twenty-nine year old toilet salesman and aspiring writer. On a Tuesday night in October, I drove my small pod-shaped car up the 405, ready for the first class. The instructor was Lou Mathews, a SoCal native who had worked as a mechanic for twenty years while quietly becoming one of the best writers in Los Angeles. (His novel, LA Breakdown, about the eastside street racing scene in the late sixties, is a lost classic that needs to come back into print immediately). In his “pastoral letter” to the class, Lou told us that we would be talking about a “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” I had read this story multiple times, just not with the eyes of a writer. On that first night of class, I prepared any number of intelligent things to say about the story, but when we discussed it, Lou wouldn’t let anyone talk about what the story meant. Instead, he just asked us to name all the characters. There are lots of characters in the story, but we remembered all of them. “What’s the cat’s name?” he asked, and everyone called out, “Pitty Sing.” Then he asked us what all the characters were wearing. Strangely, we all knew. O’Connor’s story had stayed with us not because of the plot or the way she deployed themes of evil and redemption, but because we all remembered that Bailey wore a yellow sport shirt with bright blue parrots on it. I had never talked about a story like this. It was the most simple thing in the world but it transformed my understanding of fiction.

Later Lou handed out copies of O’Connor’s essays, “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” and “Writing Short Stories.” The first time I read these, I did so in a state of complete embarrassment, as O’Connor held a mirror to all my sins. The other feeling was intimidation: she spoke with such divine clarity and certainty, as if her vision was something that had been revealed to her from on high. Every word seemed liked gospel truth. I spent sixteen years in Catholic schools, which means I can’t quote a single passage from the Bible. However, passages from Mystery & Manners are always bouncing around in my head as daily reminders, or prayers:

Like so many rugby players and mechanics before me, I submitted myself to the teachings of St. Flannery. So much so that my baseline feeling as a writer is a gnawing sense that somehow, no matter how hard I’m trying, I’m letting her down. On more than one occasion I’ve copied out her stories by hand and last summer, in ungodly heat, I made my first pilgrimage to Andalusia.

This past fall I picked up Paris Trout by Pete Dexter. From page one it’s a crazy and brutal novel, and eventually it all leads to Trout getting “arrested” for refusing to grow a beard in honor of his town’s sesquicentennial celebration. After being put in “stocks,” he comes back to the courthouse and shoots two lawyers dead. “Hey,” I thought, “that’s just like ‘The Partridge Festival’!” Later I would find out that Pete Dexter had also grown up in Milledgeville, and that he and O’Connor had been inspired by the same real life event. In 1953, a man named Marion Stembridge, after getting “arrested” for the same whimsical crime, had shot up the courthouse. But first I went back to the “The Partridge Festival,” which I hadn’t read in over a decade. I just wanted to see how the two stories compared, Singleton vs. Paris Trout. So once again, I met up with Calhoun, followed him around town, but then I got to the section in which he and Mary Elizabeth debate the best way to tell Singleton’s story. I had long forgotten what they actually talked about and now, having in the meantime embraced Mystery & Manners as a holy text, I couldn’t believe what I was reading:

I laughed out loud. O’Connor had taken her most dearly held beliefs about the art of fiction, which in turn were my most dearly held beliefs, along with countless acolytes just like me, and she had put them into the mouth of a complete jackass. I couldn’t get mind around this. It was strange and hilarious and even a little – please forgive me for using the word – meta. Why had she done this?

No one would call “The Partridge Festival” one of O’Connor’s best stories, but she seemed to have a particularly low opinion of it. In a letter to Cecil Dawkins from 1960, she writes:

“The Partridge Festival” is a minor piece, but it’s dark and funny as hell and it provides a rare glimpse of O’Connor collapsing in on herself, like the rest of us. Her work is lasting and serious precisely because she had a sense of humor. She took her art seriously, but never herself.

I was introduced to Flannery O’Connor by a giant rugby player with a shaved head. He was my freshman year RA at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. We never spoke a word to each other, but one day I heard him talking to a friend about a writing class he was in, and how he had spent much of his Christmas break copying out a bunch of Flannery O’Connor stories, word for word. “Why?” his friend asked, faintly horrified, and the rugby player said, “So I can see how she does it.” The friend still looked aghast, and I felt the same way. This seemed like a colossal waste of time, a grim and pointless chore. It would be a long time before I actually knew anything about Flannery O’Connor, or read any of her work, or started to think about myself as a fiction writer, but I never forgot the image of this hulking bald dude, bent over a table, copying out her sentences. What was it about this woman that inspired such monastic devotion?

The summer after I graduated from college I lucked into a job at a newspaper. I worked ghoulish hours on the sports desk, three o’clock until eleven. Wired after the deadline rush, I’d stay up until four or five in the morning, watching ungodly amounts of bad TV, and, occasionally, reading. At some point I picked up The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor – that beautiful FSG edition, with the three peacock feathers symbolizing the undivided substance and co-eternal majesty of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But mainly they’re just blue-green peacock feathers and they look really nice set off against the white background and gold lettering. Late at night, with Sportscenter on mute and a plate of microwaved nachos by my side, I made my way through these stories, in no particular order. I began reading in the kind of solemn mood I thought one had to bring to a Major Work of Literature, especially one written by a woman who had died tragically at the height of her powers, but this fell away once I figured out, fairly quickly, that as a writer, O’Connor was, above all things, fucking hilarious. One story in particular stood out to me: “The Partridge Festival.”

Calhoun, a twenty-three year old air conditioning salesman and aspiring writer, has driven, in his “small pod-shaped car,” to the town of Partridge, where he plans to stay a few nights with his great aunts – “box-jawed old ladies who looked like George Washington with his wooden teeth in.” They think he is there to enjoy the annual Azalea Festival, but really he has come to learn more about the man, Singleton, whose actions had recently put the town’s impending jubilation under threat:

Ten days before the festival began, a man named Singleton had been tried by a mock court on the courthouse lawn for not buying an Azalea Festival Badge. During the trial he had been imprisoned in a pair of stocks and when convicted, he had been locked in the “jail” together with a goat that had been tried and convicted previously for the same offense. The “jail” was an outdoor privy borrowed for the occasion by the Jaycees. Ten days later, Singleton had appeared in a side door on the courthouse porch and with a silent automatic pistol, had shot five of the dignitaries seated there and by mistake one person in the crowd. The innocent man had received the bullet intended for the mayor who at that moment had reached down to pull up the tongue of his shoe.We learn that Calhoun has nothing but contempt for his aunts and the rest of the town. He secretly identifies with Singleton, whom he considers a misunderstood hero driven to violence by the benighted citizens of Partridge. With plans to write a stinging expose of the town’s ignorance and hypocrisy, he walks around asking people what they think of Singleton, but he doesn’t really listen to what anyone has to say. Instead, he just gives his own thunderous opinions. At one point he takes it upon himself to enlighten a teenage boy working a soda fountain:

“An unfortunate incident,” his Aunt Mattie said. “It mars the festive spirit.”

“Singleton was only the instrument,” Calhoun said. “Partridge itself is guilty.” He finished his drink in a gulp and put down the glass.

The boy was looking at him as if he were mad. “Partridge can’t shoot nobody,” he said in a high exasperated voice.

After speaking to a few more people, Calhoun decides that the only way he can do justice to Singleton’s story is by writing a novel. Before he can do this, however, his aunts set him up on a date with a neighbor girl, Mary Elizabeth. Calhoun deigns to go for a walk with her. Looking at her round childish face, he concludes that she is retarded. But then, to his great annoyance, he finds out that she is, in fact, an aspiring intellectual and writer, and that she too hates the town and believes in the innocence and heroism of Singleton. From there they engage in an epic pissing contest, arguing over who understands Singleton more, and who should be allowed to write his story. O’Connor often has a field day with frustrated intellectuals, but Calhoun and Mary Elizabeth stand out as perhaps her most pompous and insufferable creations. Eventually they decide to go visit Singleton at the insane asylum. The brief meeting, which doesn’t go quite how they imagined, is one of the funniest moments in the collected stories, and for a long time it’s what I always remembered most about “The Partridge Festival.”

* * *

Later Lou handed out copies of O’Connor’s essays, “The Nature and Aim of Fiction” and “Writing Short Stories.” The first time I read these, I did so in a state of complete embarrassment, as O’Connor held a mirror to all my sins. The other feeling was intimidation: she spoke with such divine clarity and certainty, as if her vision was something that had been revealed to her from on high. Every word seemed liked gospel truth. I spent sixteen years in Catholic schools, which means I can’t quote a single passage from the Bible. However, passages from Mystery & Manners are always bouncing around in my head as daily reminders, or prayers:

Fiction operates through the senses.

Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t write fiction.

You can do anything you can get away with, but nobody has ever gotten away with much.

A story always involves, in a dramatic way, the mystery of personality.

Like so many rugby players and mechanics before me, I submitted myself to the teachings of St. Flannery. So much so that my baseline feeling as a writer is a gnawing sense that somehow, no matter how hard I’m trying, I’m letting her down. On more than one occasion I’ve copied out her stories by hand and last summer, in ungodly heat, I made my first pilgrimage to Andalusia.

* * *

“Listen,” Calhoun said fiercely, “get this through your head. I’m not interested in the damn festival or the damn azalea queen. I’m here only because of my sympathy for Singleton. I’m going to write about him. Possibly a novel.”

“I intend to write a non-fiction study,” the girl said in a tone that made it evident fiction was beneath her.

They looked at each other with open and intense dislike. Calhoun felt that if he probed sufficiently he would expose her essential shallowness. “Since our forms are different,” he said, again with his ironical smile, “we might compare findings.”

“It’s quite simple,” the girl said. “He was the scapegoat. While Partridge flings itself about selecting Miss Partridge Azalea, Singleton suffers at Quincy. He expiates…”

“I don’t mean abstract findings. Have you ever seen him? What did he look like? The novelist is not interested in narrow abstractions – particularly when they’re obvious. He’s…”

“How many novels have you written?” she asked.

“This will be my first,” he said coldly. “Have you ever seen him?”

“No,” she said, “that isn’t necessary for me. What he looks like makes no difference – whether he has brown eyes or blue – that’s nothing to a thinker.”

“You are probably,” he said, “afraid to look at him. The novelist is never afraid to look at the real object.”

“I would not be afraid to look at him,” the girl said angrily, “if it were at all necessary. Whether he has brown eyes or blue is nothing to me.”

“There is more to it,” Calhoun said, “than whether he has brown eyes or blue. You might find your theories enriched by the sight of him. And I don’t mean by finding out the color of his eyes. I mean your existential encounter with his personality. The mystery of personality,” he said, “is what interests the artist. Life does not abide in abstractions.”

I laughed out loud. O’Connor had taken her most dearly held beliefs about the art of fiction, which in turn were my most dearly held beliefs, along with countless acolytes just like me, and she had put them into the mouth of a complete jackass. I couldn’t get mind around this. It was strange and hilarious and even a little – please forgive me for using the word – meta. Why had she done this?

I finally finished that farce [“The Partridge Festival”] and made it less objectionable from the local standpoint…So I told Elizabeth to send it to the Critic – a Catholic book-review magazine which is going to start publishing fiction in the fall. They took it, much to my surprise, and paid $400 for it.First of all, a Catholic book review magazine paying $400 for a short story? In 1960? I’m pretty sure that’s like $20,000 in today’s economy. I checked to see if The Critic was still around, but sadly it folded a long time ago. In any case, O’Connor later removed the story, or farce, from the final manuscript of Everything That Rises Must Converge. I hold farce in high regard, so I’m glad her literary executors included “The Partridge Festival” in The Complete Stories, but I’m also grateful because it gave me a moment to see Flannery O’Connor as a struggling, self-loathing writer, and not a supernatural being. I pictured her going over her essays and thinking, “Good Lord! I’m full of shit!” And so, sick of herself, she sits down and starts writing about Calhoun. I recently read Carlene Bauer’s graceful epistolary novel, Frances and Bernard, which centers on the relationship between two writers not unlike Flannery O’Connor and Robert Lowell. In Frances, we get to see a devout and singular personality with a cutting wit, but one who is coming to understand life and art not through revelation but through the grueling and intensely human process of trial and error.

“The Partridge Festival” is a minor piece, but it’s dark and funny as hell and it provides a rare glimpse of O’Connor collapsing in on herself, like the rest of us. Her work is lasting and serious precisely because she had a sense of humor. She took her art seriously, but never herself.