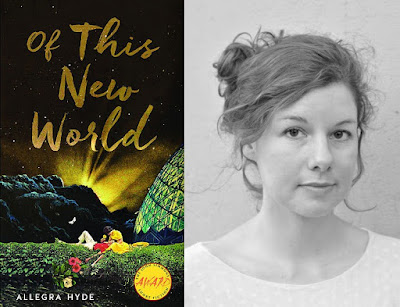

In the 45th in a series of posts on 2016 books entered for The Story Prize, Allegra Hyde, author of Of This New World (University of Iowa Press), explores some visual art principles that serve writers well.

1. Give Weight to Negative Space. When drawing or painting, the territory around a subject can be as interesting and active as the subject itself. Likewise, in writing, it is useful to remember that a story’s setting does not have to merely exist as a backdrop. The “negative space” of a story can be brought into focus for a more dynamic narrative.

2. Green is Difficult. The human eye is most sensitive to green frequencies. We have evolved to parse the many shades present in nature—olive, emerald, yellowy-lime—which means using green paint straight from the tube will look artificial. A parallel problem in writing is the challenge of describing a subject such as love. Fictional representations often come off as cliché, because most people are deeply attuned to the many shades of human intimacy. Getting love right in a story, like the color green in a painting, means being as specific as possible and honoring the need for a custom “mix.”

3. Underpainting Can Be Important. Old masters like Johannes Vermeer often used monochromatic underpaintings as a guiding framework the way some writers use outlines. Having a base scaffolding upon which to build allows both painters and writers to transition from broad gestures to successively detailed layers. Underpaintings don’t have to be completely hidden, however. Vermeer liked the way exposed portions of his ultramarine sketches would vibrate, visually, against the warmer tones of subsequent layers. Writers might consider what it could mean to juxtapose a base narrative of a particular genre or style against surprising variations in tone.

|

| Verneer's The Art of Painting |

4. Copying Masters Makes You Better. Visit any major art museum and you’ll see visitors with sketchbooks, copying Caravaggio’s shadowy ensembles or O’Keefe’s floral close-ups. Sometimes it takes the act of replication to reveal the secret mechanics of a painting: how the composition hangs together, the interplay of light and dark. As writers, we can also inhabit the work of literary masters. Conscientiously copying out passages from The Bluest Eye or Pale Fire can teach us about pacing, syntax, style, and techniques that may have otherwise remained invisible. Then we can use these techniques in our own efforts.

5. Be Patient. Sometimes you have to wait for paint to dry before you continue working on a canvas. Likewise, writers may have to let a manuscript sit for days, weeks, years, in a desk drawer before returning to it for further revision. That’s just part of the process.

6. Don’t Inhale Paint Thinner. This is general life advice.