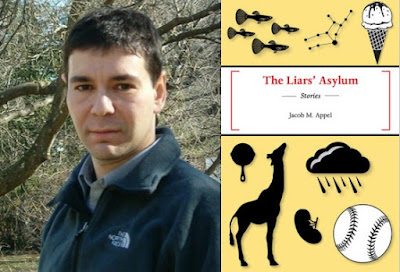

In the 13th in a series of posts on 2017 books entered for The Story Prize, Jacob M. Appel, author of The Liars' Asylum (Black Lawrence Press), lists a few things writers can do to give back.

I am frequently asked to give advice to aspiring writers—which usually means offering whatever limited wisdom I have on how to craft better stories, secure agents and publishers, and increase book sales. All of these are reasonable goals, likely shared by the overwhelming majority of readers of this post. Yet as a professional ethicist, I thought I might tackle this subject differently this time around and offer some tips on how to make the literary world a better place:

1. Be Positive or Be Quiet

I am proud to say that I have never written a negative book review, either for publication or on sites such as Amazon, Goodreads, Librarything, etc. You shouldn’t either. Any literary work you encounter was once someone else’s baby, a beloved repository for another human being’s imagination and emotion. Needless to say, some of these metaphorical babies grow up to be admirable adults—and others, quite frankly, do not. But what possible good comes of denigrating them once they are in print? If you don’t admire a work, not reviewing it at all is statement enough. With so many wonderful books on the market, any time or space spent penning a negative review occurs at the expense of other great works deserving of exposure.

2. Donate Books

Not everyone is James Paterson and capable of providing millions of dollars in seed money to public libraries, but most writers can afford to give away a few free books—or, at least, ebooks—to worthy individuals, causes, and institutions. Generosity starts at your local public library. Ask the librarians if they’d like free copies of your forthcoming book; if they tell you they have it on order already, ask that they cancel the order and provide them with the copies at no cost instead. Maybe suggest the work of an emerging or marginalized author they might purchase with the savings. Send copies of your latest volumes to charitable auctions, book drives, schools, hospitals, and nursing homes. You need not spend a fortune: even one or two copies a month, over time, can make a difference without breaking your piggy bank.

3. Thank Other Writers

I do not mean to thank them for doing you favors such as writing generous reviews or offering blurbs—although obviously, one should do that too. I mean thank them for being good writers. If you read a story or novel that you admire, send a brief email message to the author telling him or her so. A kind word from the ether never hurts, and on occasion, I have struck up wonderful friendships with fellow authors that originated in a complimentary note. And, needless to say, blurb liberally. I do not blurb every manuscript I read, or even read every manuscript I am sent, but I at least try to read an opening chapter or two whenever possible.

4. Thank Your Readers

The easiest and least costly way to thank your readers is to answer their correspondence. I suppose that may be difficult if you are one of the dozen or so authors likely to be recognized in a public place, or a serial killer with a best-selling memoir, but most of us mere mortals do not receive enough mail to require secretarial assistance. Another way to say “thank you” is to give freebees to fans: free PDFs or signed galleys always make welcome appreciation gifts. Even an email, letting a reader know you’ll be speaking or signing books in her state or city, can show gratitude for a kind review or fan letter.

5. Do Not Complain

The literary life is tough – on the pocketbook, on the ego and on the soul. But if you had wanted an easy job, you’d have become a neurosurgeon or an astronaut. While it is certainly acceptable to point out structural inequities in the publishing system, far less palatable are personal jealousies or claims of individual victimization. Bear rejection gracefully. Admire candles that burn brighter than your own. We’d all like to be Toni Morrison or Philip Roth—but nobody is owed that success. Not even if he or she pens a brilliant book. Being published, and being read, is not a right, but a privilege.

There is a lot of incivility in the world today. Sometimes it feels as though anger is the new national currency. But in the literary community, at least, that need not be the case. And any writer, no matter obscure, has a part to play: The wheels of fate may decide whether you are eulogized as a brilliant writer, but each of us has the power to determine whether we are remembered decent and virtuous literary citizens.

I am frequently asked to give advice to aspiring writers—which usually means offering whatever limited wisdom I have on how to craft better stories, secure agents and publishers, and increase book sales. All of these are reasonable goals, likely shared by the overwhelming majority of readers of this post. Yet as a professional ethicist, I thought I might tackle this subject differently this time around and offer some tips on how to make the literary world a better place:

1. Be Positive or Be Quiet

I am proud to say that I have never written a negative book review, either for publication or on sites such as Amazon, Goodreads, Librarything, etc. You shouldn’t either. Any literary work you encounter was once someone else’s baby, a beloved repository for another human being’s imagination and emotion. Needless to say, some of these metaphorical babies grow up to be admirable adults—and others, quite frankly, do not. But what possible good comes of denigrating them once they are in print? If you don’t admire a work, not reviewing it at all is statement enough. With so many wonderful books on the market, any time or space spent penning a negative review occurs at the expense of other great works deserving of exposure.

2. Donate Books

Not everyone is James Paterson and capable of providing millions of dollars in seed money to public libraries, but most writers can afford to give away a few free books—or, at least, ebooks—to worthy individuals, causes, and institutions. Generosity starts at your local public library. Ask the librarians if they’d like free copies of your forthcoming book; if they tell you they have it on order already, ask that they cancel the order and provide them with the copies at no cost instead. Maybe suggest the work of an emerging or marginalized author they might purchase with the savings. Send copies of your latest volumes to charitable auctions, book drives, schools, hospitals, and nursing homes. You need not spend a fortune: even one or two copies a month, over time, can make a difference without breaking your piggy bank.

|

| James Patterson: Super-mensch |

3. Thank Other Writers

I do not mean to thank them for doing you favors such as writing generous reviews or offering blurbs—although obviously, one should do that too. I mean thank them for being good writers. If you read a story or novel that you admire, send a brief email message to the author telling him or her so. A kind word from the ether never hurts, and on occasion, I have struck up wonderful friendships with fellow authors that originated in a complimentary note. And, needless to say, blurb liberally. I do not blurb every manuscript I read, or even read every manuscript I am sent, but I at least try to read an opening chapter or two whenever possible.

4. Thank Your Readers

The easiest and least costly way to thank your readers is to answer their correspondence. I suppose that may be difficult if you are one of the dozen or so authors likely to be recognized in a public place, or a serial killer with a best-selling memoir, but most of us mere mortals do not receive enough mail to require secretarial assistance. Another way to say “thank you” is to give freebees to fans: free PDFs or signed galleys always make welcome appreciation gifts. Even an email, letting a reader know you’ll be speaking or signing books in her state or city, can show gratitude for a kind review or fan letter.

5. Do Not Complain

The literary life is tough – on the pocketbook, on the ego and on the soul. But if you had wanted an easy job, you’d have become a neurosurgeon or an astronaut. While it is certainly acceptable to point out structural inequities in the publishing system, far less palatable are personal jealousies or claims of individual victimization. Bear rejection gracefully. Admire candles that burn brighter than your own. We’d all like to be Toni Morrison or Philip Roth—but nobody is owed that success. Not even if he or she pens a brilliant book. Being published, and being read, is not a right, but a privilege.

There is a lot of incivility in the world today. Sometimes it feels as though anger is the new national currency. But in the literary community, at least, that need not be the case. And any writer, no matter obscure, has a part to play: The wheels of fate may decide whether you are eulogized as a brilliant writer, but each of us has the power to determine whether we are remembered decent and virtuous literary citizens.