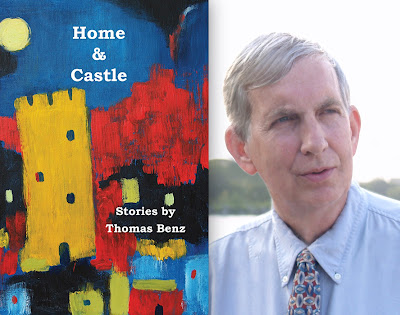

In the 11th in a series of posts from authors of 2018 books entered for The Story Prize, Thomas Benz, author of Home and Castle (Snake Press Nation), opines on the current reliance on shorthand, images, and symbols.

By its very nature, fiction helps cultivate and preserve language as the primary means of apprehending the world. Lately, however, I find myself wondering if the written word is under attack as never before from visual and social media, which also present ideas, but with a flashier immediacy. I don’t think this notion is simply nostalgia for yesteryear’s slower pace of transmission, which allowed for more in-depth forms of dialog. It is not out of mourning for the typewriter, the personal letter, for cursive handwriting and rotary phones, perhaps imbued with the aura of one’s youth. Rather, I wonder if our ever more sophisticated visual content threatens to compress and degrade the content of our speech.

Whether the attack comes in the form of movie special effects that often overwhelm the screenplay or a novel that comes with regular illustrations, the message is that words alone are not enough. Even our newspapers and magazines, once a bastion of sentences, punctuated with the occasional photo, are filling up with little films. Emojis, no matter how cute or detailed cannot transmit the rich possibilities of emotion contained in a well-chosen verb. At best, they are crude substitutes of expression, ones that require neither genuine thought nor accuracy. They seem to invite us to return to the days of painting on cave walls as a means of getting a point across.

Never has there been a time when it was more important to know the truth about what surrounds us. And yet concurrent with this, the means to deceive, based largely on the allure of speed and convenience, continue to multiply and gain acceptance. Through the use of memes that amount to slogans, and images that can be altered to any desired effect, the tools of propaganda and false persuasion have been sharpened. Hiding a lie has never been so facile, especially when the preeminence of words has been so undermined. By contrast, the use of longer-form writing usually offers many more clues about the substance and real purpose of a given point of view.

For over a hundred years, we have had cameras and movies, and there’s no question the artful use of both is a great boon to the world and the Internet greatly expands our horizons. The problem arises when the great rush of everything causes us to get ever lazier about how we absorb information, since passively watching a podcast or reading a bunch of acronyms is inherently less nuanced than a more elaborate exchange. While we all need a certain amount of convenience and entertainment, let’s be aware of the steady encroachment of oversimplified messages, which more easily lead us astray and threaten our discourse.

As anyone who has ever suffered through an interminable homily knows, longer is not always better. Yet the economy of a poet is not what I’m questioning. It is the imprecision with which complexity is often conveyed, as if a selfie could ever tell the whole tale. For example, nowadays literary fiction often seems relegated to the hinterland of a subcategory. Somehow it is just too difficult and requires an immersion that would cut us off too long from our incoming texts. The popularity of what is slick and swift and shallow appears to be on the ascendant.

Only language that is not artificially curtailed and remains relatively free of adornment enables the recipient to bring his or her full imagination to the encounter. A novel or collection of stories uniquely engages a reader to construct a world right along with the author, to infuse what’s been created with a unique filter, to make the abstract visible in one’s own mind.

I have no wish to assail the power of a sublime vista or the perfect frozen moment of a street corner, or anything else that can only be captured with the benefit of sight. And I’m not saying there is no place for Twitter or Instagram or the labyrinthine archives of YouTube. But just as taking pictures can be a way of outsourcing memory, we should be mindful of how easy it is to rely on simplistic methods of recording our experience and what gets lost in translation. If a “picture is worth a thousand words,” it cannot do quite the same thing as those words. In our rush to abbreviate, to go faster, to flood our senses, to live more and more, this might be something we should not allow ourselves to forget.

Whether the attack comes in the form of movie special effects that often overwhelm the screenplay or a novel that comes with regular illustrations, the message is that words alone are not enough. Even our newspapers and magazines, once a bastion of sentences, punctuated with the occasional photo, are filling up with little films. Emojis, no matter how cute or detailed cannot transmit the rich possibilities of emotion contained in a well-chosen verb. At best, they are crude substitutes of expression, ones that require neither genuine thought nor accuracy. They seem to invite us to return to the days of painting on cave walls as a means of getting a point across.

|

| Absolute bull: Then and now |

Never has there been a time when it was more important to know the truth about what surrounds us. And yet concurrent with this, the means to deceive, based largely on the allure of speed and convenience, continue to multiply and gain acceptance. Through the use of memes that amount to slogans, and images that can be altered to any desired effect, the tools of propaganda and false persuasion have been sharpened. Hiding a lie has never been so facile, especially when the preeminence of words has been so undermined. By contrast, the use of longer-form writing usually offers many more clues about the substance and real purpose of a given point of view.

For over a hundred years, we have had cameras and movies, and there’s no question the artful use of both is a great boon to the world and the Internet greatly expands our horizons. The problem arises when the great rush of everything causes us to get ever lazier about how we absorb information, since passively watching a podcast or reading a bunch of acronyms is inherently less nuanced than a more elaborate exchange. While we all need a certain amount of convenience and entertainment, let’s be aware of the steady encroachment of oversimplified messages, which more easily lead us astray and threaten our discourse.

As anyone who has ever suffered through an interminable homily knows, longer is not always better. Yet the economy of a poet is not what I’m questioning. It is the imprecision with which complexity is often conveyed, as if a selfie could ever tell the whole tale. For example, nowadays literary fiction often seems relegated to the hinterland of a subcategory. Somehow it is just too difficult and requires an immersion that would cut us off too long from our incoming texts. The popularity of what is slick and swift and shallow appears to be on the ascendant.

Only language that is not artificially curtailed and remains relatively free of adornment enables the recipient to bring his or her full imagination to the encounter. A novel or collection of stories uniquely engages a reader to construct a world right along with the author, to infuse what’s been created with a unique filter, to make the abstract visible in one’s own mind.

I have no wish to assail the power of a sublime vista or the perfect frozen moment of a street corner, or anything else that can only be captured with the benefit of sight. And I’m not saying there is no place for Twitter or Instagram or the labyrinthine archives of YouTube. But just as taking pictures can be a way of outsourcing memory, we should be mindful of how easy it is to rely on simplistic methods of recording our experience and what gets lost in translation. If a “picture is worth a thousand words,” it cannot do quite the same thing as those words. In our rush to abbreviate, to go faster, to flood our senses, to live more and more, this might be something we should not allow ourselves to forget.