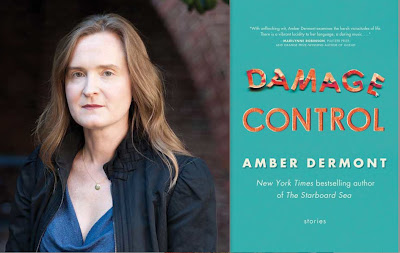

In the 29th in a series of posts on 2013 books entered for The Story Prize, Amber Dermont, author of Damage Control (St. Martin's Press), reveals how an unsatisfactory encounter with a spoiled teenager haunted her stories.

Several of the stories in Damage Control were inspired by the summers I spent teaching at a “pre-college edutainment program.” The students were from diverse backgrounds: the wealthy, the very wealthy, and the obscenely wealthy. One student—I’ll call him, Harry—was infamously affluent. His father ruled over a publishing empire (yes, such miracles exist!). Harry had his own literary aspirations. A talented drummer, he wrote poems he hoped to slap into songs. In his dormitory he set up a vintage Pearl kit and gave command performances conjuring the hotfooted lightening of John Bonham and the jazz cool of Ginger Baker. During one impromptu session, Harry spotted me in the crowd and gave a nod of approval.

Teachers are wise not to turn their students into characters. A writer’s greatest wisdom/burden is a talent for turning everyone into a character. Harry had the aloof swagger of a fortunate son and the rough-throated timbre of a smoker who’d been toking since the womb. The kid was smart, charming and high all of the time. Whenever he rode along for fieldtrips, he’d fall asleep and when I dropped him off at his dorm, he’d stare at the building and ask, “Where am I?” Harry reminded me of the careless boys I’d gone to prep school with and in my arrogance I hoped to change him. I didn’t want to write about him. I wanted to teach him something.

On a trip to Provincetown, one of the other students referred to me as, “the hired help.” Harry came to my defense. “Nah,” he said. “She’s cool. She’s one of us.” I saw nothing of myself in these children. Touring down Commercial Street, Harry asked for help picking out a skateboard. He customized a deck, trucks, bearings and wheels that cost more than my first car. Later that night, Harry expertly skateboarded past me, maneuvering around tourists, a lit cigarette in his hand. I called out to him and Harry circled back, reciting lines from the very John Berryman dream song we’d learned that week: “I am the little man who smokes and smokes.”

That summer ended in cataclysm. After a series of epic violations, Harry was expelled. As his parting salvo, he indicted a dozen classmates. While he packed and waited for his father, I babysat, berating him for narking on his friends. He shrugged. I explained honor among thieves, advised that in the future, when he found himself in trouble (and he would), he should shoulder the blame. He agreed. I waited a moment then asked if any other students were involved in the scandal. He mentioned three additional girls. I shook my head. “You’ve learned nothing.”

Harry’s father hailed a cab in Manhattan and made the three-hour/two hundred-mile journey with the meter running. The great mogul was a tiny man. Harry greeted his father with a nod, the same nod he’d given me. Not a sign of approval after all, just an indifferent acknowledgement. His father said, “Let’s get your things.”

When Harry lifted the taxi’s trunk, he realized his drums were too large. No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t make the drums fit. His father said, “Leave them. I’ll buy you a new set.” For a kid who cared about nothing, those drums meant everything. Harry looked at me. Soon he would return to his SoHo loft and squander his summer with people who would fail him forever. I saw his future and understood the depths of his doom. He was a character I knew well. He’d entered my imagination.

So, what happened next? In one account, I remain a bystander. I do nothing. Offer no assistance. The taxi pulls away and the drums remain. Maybe I tap my own music on their skins. Maybe I take the drums for myself. In another draft, I parent the misfortune. “We can fix this.” I volunteer to ship the drums home, to do the paperwork, the dirty work. Harry nods. “Cool,” he says. “You’re cool.” I’m the hired help. I’m one of us. “I am the girl who does know better but.” I’m a writer enacting a scene.

Perhaps it’s foolish to lavish lines of empathy on a spoiled child. There are so many sudden saints worthy of consideration. Maybe we are all spoiled children in search of our salvation. Stories help us reconcile what we are with what we might never be. Stories emerge from the rhythmic notations of our lives and shape our muted desires into art. For me, stories are triggered by a single image or turn of phrase I then begin to submerge and conceal from the reader. That’s the work I do. I build a story around something no one else can see: a reckless boy, an impatient father, snares and cymbals. Harry does not appear in my collection and yet his privilege, sadness and spirit haunt the stories in Damage Control.

Nowadays, Harry works for his father. From his office I imagine he has a heart-stopping view. I hope he still plays his drums. Before the music ends, here’s my tribute story, one last song: Harry, you were my student but what did I teach you? You might as well have been my son.

Several of the stories in Damage Control were inspired by the summers I spent teaching at a “pre-college edutainment program.” The students were from diverse backgrounds: the wealthy, the very wealthy, and the obscenely wealthy. One student—I’ll call him, Harry—was infamously affluent. His father ruled over a publishing empire (yes, such miracles exist!). Harry had his own literary aspirations. A talented drummer, he wrote poems he hoped to slap into songs. In his dormitory he set up a vintage Pearl kit and gave command performances conjuring the hotfooted lightening of John Bonham and the jazz cool of Ginger Baker. During one impromptu session, Harry spotted me in the crowd and gave a nod of approval.

Teachers are wise not to turn their students into characters. A writer’s greatest wisdom/burden is a talent for turning everyone into a character. Harry had the aloof swagger of a fortunate son and the rough-throated timbre of a smoker who’d been toking since the womb. The kid was smart, charming and high all of the time. Whenever he rode along for fieldtrips, he’d fall asleep and when I dropped him off at his dorm, he’d stare at the building and ask, “Where am I?” Harry reminded me of the careless boys I’d gone to prep school with and in my arrogance I hoped to change him. I didn’t want to write about him. I wanted to teach him something.

On a trip to Provincetown, one of the other students referred to me as, “the hired help.” Harry came to my defense. “Nah,” he said. “She’s cool. She’s one of us.” I saw nothing of myself in these children. Touring down Commercial Street, Harry asked for help picking out a skateboard. He customized a deck, trucks, bearings and wheels that cost more than my first car. Later that night, Harry expertly skateboarded past me, maneuvering around tourists, a lit cigarette in his hand. I called out to him and Harry circled back, reciting lines from the very John Berryman dream song we’d learned that week: “I am the little man who smokes and smokes.”

That summer ended in cataclysm. After a series of epic violations, Harry was expelled. As his parting salvo, he indicted a dozen classmates. While he packed and waited for his father, I babysat, berating him for narking on his friends. He shrugged. I explained honor among thieves, advised that in the future, when he found himself in trouble (and he would), he should shoulder the blame. He agreed. I waited a moment then asked if any other students were involved in the scandal. He mentioned three additional girls. I shook my head. “You’ve learned nothing.”

Harry’s father hailed a cab in Manhattan and made the three-hour/two hundred-mile journey with the meter running. The great mogul was a tiny man. Harry greeted his father with a nod, the same nod he’d given me. Not a sign of approval after all, just an indifferent acknowledgement. His father said, “Let’s get your things.”

|

| Drum set: not a good fit |

So, what happened next? In one account, I remain a bystander. I do nothing. Offer no assistance. The taxi pulls away and the drums remain. Maybe I tap my own music on their skins. Maybe I take the drums for myself. In another draft, I parent the misfortune. “We can fix this.” I volunteer to ship the drums home, to do the paperwork, the dirty work. Harry nods. “Cool,” he says. “You’re cool.” I’m the hired help. I’m one of us. “I am the girl who does know better but.” I’m a writer enacting a scene.

Perhaps it’s foolish to lavish lines of empathy on a spoiled child. There are so many sudden saints worthy of consideration. Maybe we are all spoiled children in search of our salvation. Stories help us reconcile what we are with what we might never be. Stories emerge from the rhythmic notations of our lives and shape our muted desires into art. For me, stories are triggered by a single image or turn of phrase I then begin to submerge and conceal from the reader. That’s the work I do. I build a story around something no one else can see: a reckless boy, an impatient father, snares and cymbals. Harry does not appear in my collection and yet his privilege, sadness and spirit haunt the stories in Damage Control.

Nowadays, Harry works for his father. From his office I imagine he has a heart-stopping view. I hope he still plays his drums. Before the music ends, here’s my tribute story, one last song: Harry, you were my student but what did I teach you? You might as well have been my son.