|

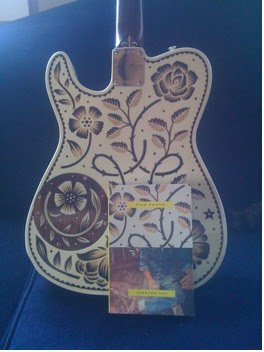

| Lea's Wild Punch and a Creston guitar |

I wrote the stories in my book, Wild Punch, over the course of sixteen years, during which time just about everything in my life changed. Among other things, I fell accidentally into making electric guitars for a living (www.crestonguitars.com). Guitar playing had always represented distraction, the false path, when I was younger and earnestly trying to write and write and write. But by my mid-twenties, I found myself playing fifty-plus shows a year with a bunch of different outfits, some ambitious, some lazy. Sooner or later, I started making guitars in my basement, and then in my garage, and then in the brick building I still occupy near the old barge canal and Superfund site in my adopted city of Burlington, Vermont. It took me a long time to make peace with myself, but eventually I faced up to the fact that I liked playing guitars, liked making guitars, and didn’t care any less about reading books and writing stories as a result. You can serve two masters, it seems.

Writing fiction and making electric guitars have nothing whatsoever to do with each other as far as I’m concerned. But I like music a lot, have always cared a little too much about it – something I could cling to, even early on when other kids were learning how to play sports or study. I’ll be 39 in December. I’ve written a lot of stories and played a lot of music but have never written a song. From my vantage, right next to music but having never written any of it, the shape of a song is intriguing and exciting to me and sometimes plays out in the shapes of my short stories.

I like those songs that depart from themselves entirely toward the end. Everybody likes the song “Seven And Seven Is” by Arthur Lee and Love, but how do you explain that quiet, guitar outtro – I suppose it’s a coda – after all the crashing and smashing of the song itself? Or the rousing, thematic, Memphis-y tail end of the otherwise quiet, painful, beautiful, live version of “Who Knows Where The Time Goes?” as sung by Nina Simone? That’s probably exit music for the singer herself – you can hear the surge of applause as she, a safe guess, comes out from the wings for another bow. But as a piece of music removed from the live taping, heard and not seen, it’s a change of direction that furthers everything that came before it.

“Who Knows Where The Time Goes?” was written by Sandy Denny, who died at 31 after falling down some stairs. She sang the 17th-century English ballad “Matty Groves” with Fairport Convention, the recorded version of which proceeds through the story of the song in a straightforward, quietly tense way. The story is good! A Lady seduces a young fellow at church while her husband is out in the far cornfields, bringing the yearlings home. The Lord catches wind of the affair and zips home, wakes them up, there’s a sword fight, young Matty Groves is killed and so is the cheating wife. The Lord calls for "a grave to put these lovers in. But bury my lady at the top for she was of noble kin." It sounds sort of Hobbity on the page, but listen: Adultery! Class warfare! Agrarian life! After four minutes of chorus-less music, the band takes off on an equally long, winding instrumental that bears nothing melodically to the sung verses—all the tension of the lyric and the steady, chugging arrangement that urged the story along with such restraint quickly explodes into a freewheeling fiddle-and-electric guitar escapade which, for all I know, is based on some other traditional English music. It’s different than what came before it but takes the listener deeper into the story by striking out in a new direction. That feels like life to me. A writing teacher once told me you may learn a lot from the funny pages. He referenced Little Lulu. I feel the same way about the music on the radio.

The linked stories in Wild Punch are my own look back at the place where I grew up on the Connecticut River, which divides New Hampshire and Vermont, and the people there. But the shape of the stories—where they start, where they go—is enormously informed by the music I was hearing at the time, none of which comes from northern New England except maybe for Dick Curless or Clarence White. It’s hard not to steal from the writers you love whether you mean to or not. But it feels less directly corrupt to take guidance from the music of Doug Sahm (specifically “She’s Huggin’ You, But She’s Lookin’ At Me”) which I do at least once in my book. I confess.

The top half of the front cover of Wild Punch shows a detail photograph of a guitar I made for a local musician a couple of years ago. He plays two hundred dates a year with it.