In the 31st in a series of posts on 2015 books entered for The Story Prize, Rebecca Makkai, author of Music for Wartime (Viking), describes her frustration with some people's reluctance to read short story collections.

I’m one of three authors at a signing table at a benefit. A woman walks up, touching each book. She gets to my story collection. “What’s this about?” she says.

I say, “It’s a collection of stories, and—”

And she goes, “Oh.” Not as in, “Oh, how interesting,” but like, “Oh, I thought the hors d’oeuvre you were passing was foie gras, but it’s Spam.” A little to the left of “Oh, no thank you, I would not care for a dead raccoon.”

And so I decide to call her on it. I make sure to laugh, and I say, “Wait, what’s that about?”

I’m not a confrontational person. It’s just that this is the 300th time this has happened to me since June, and I’ve reached a breaking point.

In November of 2013, I participated for the first time in Small Business Saturday—specifically in Sherman Alexie’s initiative for authors to hand sell books in the indies. I went to Chicago’s City Lit with a list of titles to recommend. In addition to novels and nonfiction, I was pushing three story collections—chief among them Jamie Quatro’s I Want to Show You More. I told people it was beautiful and strange and important. I showed them the gorgeous cover (silvery and festive!). I did everything but cover up the word “stories” with my thumb. Which is probably what I should’ve done. Because in two hours of selling, I moved novels and children’s books and calendars and a coffee table book on horses, but I didn’t sell a single story collection until one guy came in shopping for his girlfriend, an aspiring writer.

At this point, I’d published a novel and had another due soon; but the stories I’d been writing all along had always been just as important to me. More, possibly. I knew, in theory, that a story collection would be a hard road. Yet for every person saying stories didn’t sell, there was some unhelpful optimist going “Yes, but George Saunders is on the bestseller list!” Or “But we have such short attention spans nowadays!” (I assume the latter explains the raging resurgence of the sonnet among teenagers.)

This was my wakeup call. And in plenty of time. I was still a year and a half away from the barrage of “So this one’s just stories?” and “I only read novels,” and “My book club would never go for a collection,” and “I always skip those in The New Yorker.” I had time to steel myself. I had time to remind myself to be doubly grateful this time for every reader, for every review, for every kind bookseller who made space on the shelf. Triply grateful, in fact. Is quintuply a word?

And on the one hand, I’ve made my peace with it. Because every year I watch the Oscars, and when they announce the short films, I haven’t seen a single one. I get up and refill my wine glass. I know that I should see them, that they’re important, but as a general consumer I just don’t seek them out. And I tell myself maybe it’s the same with stories: They’re important to writers, to serious readers, but they’re not for the average palate.

But NO, NO, NO, NO, NO. Good God. People don’t know what they’re missing. Scarred by some Hawthorne story they read in high school, or maybe seeking a weeks-long immersion rather than a plunge in the icy pool, they’ve turned their backs on our newest voices, our sharpest experimentation, our wildest dreams. They’re missing out on Lydia Davis and Alice Munro. They’re missing the brilliant short work of Kevin Brockmeier and Julie Otsuka. They’re missing the faceted perfection the short form can approach. They’re missing experiments of voice and form and subject that can be maintained for 5,000 words, but not 90,000. (Who wants to read a 300-page novel about a man turning into a cockroach?)

Which is why I snap and ask this woman what she means by “Oh.”

She says, “I shouldn’t have said that! I do read stories. I do. I’ll probably buy this one.” And she turns it awkwardly over, reads the back.

I assure her I was just joking, that I know stories aren’t for everyone. We have a pleasant conversation.

She moves along the table, and when she reaches the end, she looks back to see if I’m watching. I pretend I’m not. She leaves the book right there.

I’m one of three authors at a signing table at a benefit. A woman walks up, touching each book. She gets to my story collection. “What’s this about?” she says.

I say, “It’s a collection of stories, and—”

And she goes, “Oh.” Not as in, “Oh, how interesting,” but like, “Oh, I thought the hors d’oeuvre you were passing was foie gras, but it’s Spam.” A little to the left of “Oh, no thank you, I would not care for a dead raccoon.”

And so I decide to call her on it. I make sure to laugh, and I say, “Wait, what’s that about?”

I’m not a confrontational person. It’s just that this is the 300th time this has happened to me since June, and I’ve reached a breaking point.

In November of 2013, I participated for the first time in Small Business Saturday—specifically in Sherman Alexie’s initiative for authors to hand sell books in the indies. I went to Chicago’s City Lit with a list of titles to recommend. In addition to novels and nonfiction, I was pushing three story collections—chief among them Jamie Quatro’s I Want to Show You More. I told people it was beautiful and strange and important. I showed them the gorgeous cover (silvery and festive!). I did everything but cover up the word “stories” with my thumb. Which is probably what I should’ve done. Because in two hours of selling, I moved novels and children’s books and calendars and a coffee table book on horses, but I didn’t sell a single story collection until one guy came in shopping for his girlfriend, an aspiring writer.

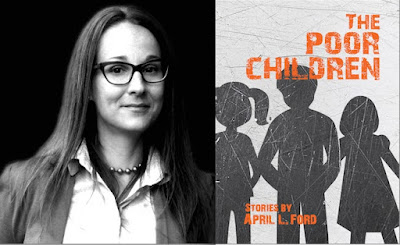

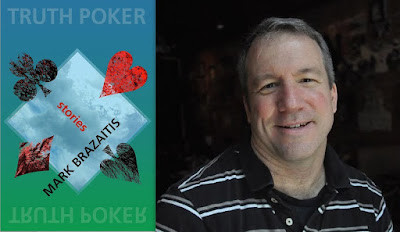

|

| Hard sell: Short story collection |

At this point, I’d published a novel and had another due soon; but the stories I’d been writing all along had always been just as important to me. More, possibly. I knew, in theory, that a story collection would be a hard road. Yet for every person saying stories didn’t sell, there was some unhelpful optimist going “Yes, but George Saunders is on the bestseller list!” Or “But we have such short attention spans nowadays!” (I assume the latter explains the raging resurgence of the sonnet among teenagers.)

This was my wakeup call. And in plenty of time. I was still a year and a half away from the barrage of “So this one’s just stories?” and “I only read novels,” and “My book club would never go for a collection,” and “I always skip those in The New Yorker.” I had time to steel myself. I had time to remind myself to be doubly grateful this time for every reader, for every review, for every kind bookseller who made space on the shelf. Triply grateful, in fact. Is quintuply a word?

And on the one hand, I’ve made my peace with it. Because every year I watch the Oscars, and when they announce the short films, I haven’t seen a single one. I get up and refill my wine glass. I know that I should see them, that they’re important, but as a general consumer I just don’t seek them out. And I tell myself maybe it’s the same with stories: They’re important to writers, to serious readers, but they’re not for the average palate.

But NO, NO, NO, NO, NO. Good God. People don’t know what they’re missing. Scarred by some Hawthorne story they read in high school, or maybe seeking a weeks-long immersion rather than a plunge in the icy pool, they’ve turned their backs on our newest voices, our sharpest experimentation, our wildest dreams. They’re missing out on Lydia Davis and Alice Munro. They’re missing the brilliant short work of Kevin Brockmeier and Julie Otsuka. They’re missing the faceted perfection the short form can approach. They’re missing experiments of voice and form and subject that can be maintained for 5,000 words, but not 90,000. (Who wants to read a 300-page novel about a man turning into a cockroach?)

Which is why I snap and ask this woman what she means by “Oh.”

She says, “I shouldn’t have said that! I do read stories. I do. I’ll probably buy this one.” And she turns it awkwardly over, reads the back.

I assure her I was just joking, that I know stories aren’t for everyone. We have a pleasant conversation.

She moves along the table, and when she reaches the end, she looks back to see if I’m watching. I pretend I’m not. She leaves the book right there.