There are two books that I’ve returned to again and again across the years, both by poets. The first is Changing Your Story by Patricia Clark Smith and the other is Crush by Richard Siken.

I first read Changing Your Story as a teenager and found my way back to it some years later, right after college. I’d just returned from Japan and was in limbo, living in Boston with my best friend while I considered the life (and the relationship) I’d left behind me, stacked against my hopes for my life back in the U.S. I read poems out loud to my friend while we cooked, while we did laundry, while she studied for her med school exams. The book spoke to me in a new way. I was raised in many countries, raised with the constant fact of our ability to transform. Change your language, change your geography, change your customs, and there it is: a new iteration of yourself, a new story. No matter what you take with you from country to country, there is also so much that must get left behind—no matter how you try to hold on. In the wake of my recent leaving, the poems reminded me that transformation is as human and inexorable as breathing. Patricia Clark Smith seemed to understand this better than anyone, although these poems are so deeply rooted in the texture and detail of her home state of New Mexico, in her identity as a Native woman. My transience and her rootedness, my uncertainty and her certainty, were two sides of the same coin.

Conversely, Richard Siken’s poems found me at a moment when I was coming to terms with my queer identity – and, with it, the wary questions I was receiving from people both straight and gay. Queer is a fluid construct, by necessity, and fluidity is so often distrusted. As someone whose entire identity is a confluence of fluidities (both national and sexual), I was compelled by Siken’s work in a way that, even now, is hard to articulate. His poems offered no comfort other than the feeling of being witnessed—which is, of course, sometimes the only comfort. It is raw painful work, each poem a hard-won confession, a grappling with confusion, bewilderment, grief, violence, and queerness into which all these things are folded—and with it, defiance as well. Over the years I return to this collection, still amazed by how it propels itself forward, how it generates an electricity born of urgency. I don’t carry the same rawness that I first did; I’ve become much more comfortable with the discomfort that queerness can generate even within my own community. But I still feel like something in those poems sees me clearly—like the poems and I are sharing a long look of recognition.

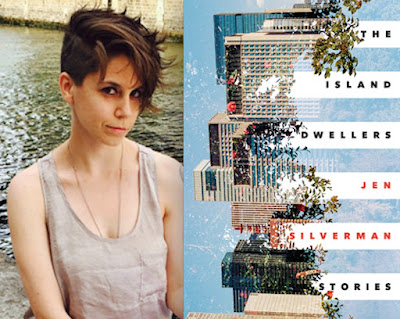

The poems in both books read like short stories, confessions, perhaps even monologues, with the same attention to rhythm and voice that you find in good theatre. I’ve worked in theatre for the past decade, and it was in and around writing plays that I wrote my first story collection, The Island Dwellers. I can’t help but think that both of these poets influenced my approach to writing prose and plays. There’s nothing more powerful than a piece of art that functions like a shared secret, like a letter delivered directly to the one person in the audience who needs to receive it. What is writing if not an overture to strangers moving through the world, who might need what you need and long for what you long for? What is writing if not a chance to surrender the small lies that get us through each day, and risk coming face to face with your unguarded self?