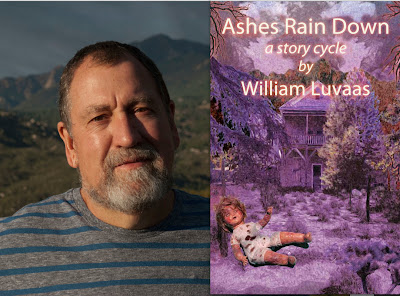

In the 10th in a series of posts on 2013 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, William Luvaas, author of Ashes Rain Down (Spuyten Duyvil), discusses what sparks his interest and his stories.

How does a story get started? It differs for each of us, of course. Mine begin with some spark—an image, phrase, place, person, or experience—which falls into the tinder of ideas, themes, and subjects that interest me. Such sparks are fragile and ephemeral; I must get them down on paper before they vanish. There are stories that appear mysteriously, welling up from the unconscious mind as if already written there. But most have a specific inception and grow out of it.

The initiating spark can be an image, say of ashes floating down from the sky, or Katherine Anne Porter’s glimpse of a girl through a window with an open book in her lap that “set up a commotion in my mind,” as she put it, and sparked her story “Flowering Judas.” In time, we develop an instinct for recognizing promising images.

Or a story may start with a phrase we find intriguing. I will set out blindly, having no idea where this initial phrase may lead me, trusting it will lead me somewhere. A door is opened into the story and the words rush in. Take the phrase, “Lately, we have been plagued by flies....” The mind seizes upon this concept: Flies are symbolic of death and decay, plagues of them cannot be a good omen, this will not be a lighthearted story.

Places can be generative, as they were for Eudora Welty and William Faulkner. Setting suggests atmosphere, and together they suggest characters—as if our landscape comes ready peopled with them, a story line follows. Stories often grow from the soil in which they take root. In Faulkner’s “Barn Burning,” a tenant farmer with a grudge against his landlord limps along a dirt road toward the landowner’s mansion, wearing an “ironlike black coat,” his profile like “something cut ruthlessly from tin.” He seems part and parcel of the Mississippi landscape.

My stories are often set in places where I am living. In Upstate New York, my characters were cold and isolated. Bad weather was deterministic in their lives, sometimes fatal. My stories set in Mendocino in Northern California are rain-soaked, characters move spectrally through fog rolling in off the Pacific, drifting through the redwoods. Living as I do now in Southern California’s high desert, I find dry Santa Ana winds blowing dust through my work, coyotes howl in the distance, the sun is white hot at midday, the sky endlessly blue. Forces of life and death chafe against one another, suggesting stark, dramatic story lines and rugged, feisty characters.

The elements affect both the inner and outer landscapes of my characters and symbolize conflicts in their lives. It’s an unconscious rather than a conscious influence, likely informed by my belief that nature and blind fate shape our lives more than we know. We haven’t half the control we believe we have. My characters are often in for a bumpy, unpredictable ride.

There is the influence of people we’ve known, our life experiences, and stories we have heard. While these may help initiate or inform a story, we shouldn’t be enslaved by them. Beginning writers often think it easier to retell a true-life narrative than to invent a new one. But such works often don’t come to life or the writer loses interest in them. Since he/she already knows the outcome, there will be no joy in discovering it. Fiction, after all, is fantasy (not necessarily lighthearted) that mimics life. If we don’t allow our imagination to breathe, our story may well die of asphyxiation. Stories must find a life of their own.

Sometimes I don’t at first recognize the real events and people who creep into my work. They appear in altered guises, as people do in dreams. Experiences are improved upon, transformed, woven into other strands in the narrative. Characters taken from life change clothes and habits, take new lovers and jobs—only distantly related to the people they are modeled on. They usually appear unbidden like volunteers in a garden.

All this to suggest that the found objects in our lives—places, events, people, poignant imagery—can feed the imagination and give birth to our stories. But only when mixed with creative fancy do they bring a story to life. There’s no predicting what will spark a story. It’s a mysterious and individuated business. That girl sitting with a book in her lap might not mean anything to another writer, but she stirred up ideas already gestating in Porter’s mind, and the story sprang out of her as if from the head of Zeus.

How does a story get started? It differs for each of us, of course. Mine begin with some spark—an image, phrase, place, person, or experience—which falls into the tinder of ideas, themes, and subjects that interest me. Such sparks are fragile and ephemeral; I must get them down on paper before they vanish. There are stories that appear mysteriously, welling up from the unconscious mind as if already written there. But most have a specific inception and grow out of it.

The initiating spark can be an image, say of ashes floating down from the sky, or Katherine Anne Porter’s glimpse of a girl through a window with an open book in her lap that “set up a commotion in my mind,” as she put it, and sparked her story “Flowering Judas.” In time, we develop an instinct for recognizing promising images.

Or a story may start with a phrase we find intriguing. I will set out blindly, having no idea where this initial phrase may lead me, trusting it will lead me somewhere. A door is opened into the story and the words rush in. Take the phrase, “Lately, we have been plagued by flies....” The mind seizes upon this concept: Flies are symbolic of death and decay, plagues of them cannot be a good omen, this will not be a lighthearted story.

Places can be generative, as they were for Eudora Welty and William Faulkner. Setting suggests atmosphere, and together they suggest characters—as if our landscape comes ready peopled with them, a story line follows. Stories often grow from the soil in which they take root. In Faulkner’s “Barn Burning,” a tenant farmer with a grudge against his landlord limps along a dirt road toward the landowner’s mansion, wearing an “ironlike black coat,” his profile like “something cut ruthlessly from tin.” He seems part and parcel of the Mississippi landscape.

|

| Mendocino: The foggiest notion |

The elements affect both the inner and outer landscapes of my characters and symbolize conflicts in their lives. It’s an unconscious rather than a conscious influence, likely informed by my belief that nature and blind fate shape our lives more than we know. We haven’t half the control we believe we have. My characters are often in for a bumpy, unpredictable ride.

There is the influence of people we’ve known, our life experiences, and stories we have heard. While these may help initiate or inform a story, we shouldn’t be enslaved by them. Beginning writers often think it easier to retell a true-life narrative than to invent a new one. But such works often don’t come to life or the writer loses interest in them. Since he/she already knows the outcome, there will be no joy in discovering it. Fiction, after all, is fantasy (not necessarily lighthearted) that mimics life. If we don’t allow our imagination to breathe, our story may well die of asphyxiation. Stories must find a life of their own.

Sometimes I don’t at first recognize the real events and people who creep into my work. They appear in altered guises, as people do in dreams. Experiences are improved upon, transformed, woven into other strands in the narrative. Characters taken from life change clothes and habits, take new lovers and jobs—only distantly related to the people they are modeled on. They usually appear unbidden like volunteers in a garden.

All this to suggest that the found objects in our lives—places, events, people, poignant imagery—can feed the imagination and give birth to our stories. But only when mixed with creative fancy do they bring a story to life. There’s no predicting what will spark a story. It’s a mysterious and individuated business. That girl sitting with a book in her lap might not mean anything to another writer, but she stirred up ideas already gestating in Porter’s mind, and the story sprang out of her as if from the head of Zeus.