In the 36th in a series of posts on 2017 books entered for The Story Prize, Douglas Trevor, author of The Book of Wonders (SixOneSeven Books), discusses how Toni Morrison influenced his writing when he took an undergraduate writing class with her.

When I was a junior at Princeton in the spring of 1991, I had the opportunity to take a small craft class on fiction writing with Toni Morrison. There were six of us in the class—all students in the creative writing program. We met once a week in Professor Morrison's spacious office in a building known to us simply by its street address: 185 Nassau. In addition, Professor Morrison scheduled individual appointments with us. This was two years before she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In one of my private meetings with Professor Morrison, I remember her asking if I had first drafted the story we were discussing by hand or if I had typed it directly into my computer. At the time, I was using a Macintosh SE that had dual floppy drives. I recall writing my stories on this computer, saving them on a floppy disk, and then printing them out in the computer lab in Fine Library. I told her all this, adding that my own handwriting was so bad, sometimes I had difficulty deciphering my lecture notes.

She responded by shaking her head and laughing very softly. She said I had to be able to read my own handwriting if I wanted to be a serious writer; otherwise, I would never learn how to control and create the music of my sentences. She told me to rewrite the story by hand and then revise it and rewrite it again. Typing, she observed, is not the same as writing.

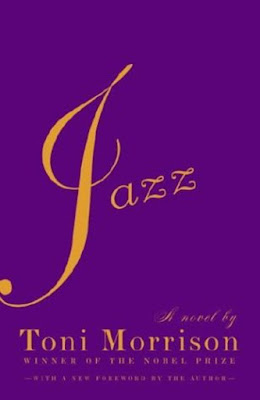

Perhaps none of Morrison's novels are more overtly attentive to the question of rhythm and variation than Jazz, which would come out in 1992—a year after my class with Professor Morrison ended. In Jazz, the distinct narrative perspective on each character is akin to a different solo. Taken together, these solos form a larger, composite piece, all knitted together—orchestrated, as it were—by the narrator.

Perhaps none of Morrison's novels are more overtly attentive to the question of rhythm and variation than Jazz, which would come out in 1992—a year after my class with Professor Morrison ended. In Jazz, the distinct narrative perspective on each character is akin to a different solo. Taken together, these solos form a larger, composite piece, all knitted together—orchestrated, as it were—by the narrator.I find the theory of character development embodied by Jazz to be an incredibly generative model for thinking about fiction writing, not just because it emphasizes how characters need to sound different from one another, and how this acoustic distance is part of what establishes character in the first place, but also because Morrison thinks about the historical dimensions that inform how and why characters express themselves in unique ways. By historical dimensions, I don't mean that older characters will use different forms of speech and diction than their younger counterparts, although of course that's true, but that each character should have a different relationship to history. This history can be personal or political or—as is really always the case in Morrison—both.

The title story of my recent collection, The Book of Wonders, is just one example of how Toni Morrison's lessons about character development, and her emphasis on subjective histories, continue to shape my writing more than twenty years later. In this story, a middle-aged woman named Simone is convinced that her mother, Annabel, has long scribbled secrets about her past in a leather ledger book she keeps under lock and key. For Simone, to access this book is to access a secret history that will help her explain the distance that has always existed between her and her mother. Annabel, on the other hand, regards the past in very different terms. Never really satisfied in marriage, she has instead dwelt upon the memories she has of those female friendships she cultivated while a student at Radcliffe in the sixties. Annabel has chosen to live in these memories—to clutter her home with pictures of these women, and to judge her daughter in relation to these figures.

While Simone assumes that excavating her mother's real past will prove something incontrovertible about it, and therefore explain their own relationship in some fundamental way, what she discovers instead is not so much what her mother thought about the past but how she thought about her own life. This discovery has a much different impact on Simone than she would have ever imagined.

"The Book of Wonders," both the story and the collection, is about this kind of impact—about what happens when one character is made to understand how another character sees the past. By virtue of her sustained meditation on how history works in the minds of different people, I group Toni Morrison with other writers whose work has meant the word to me—other writers for whom the flickering and repressing of the past constitutes one of their central concerns: Proust, Woolf, Marquez, Sebald, Bolaño, and—more recently—Egan. That I had the opportunity to engage directly with Professor Morrison's mind, to watch her pen mark my pages, is something—to this day—I still cannot quite believe.