In the 66th in a series of posts on 2016 books entered for The Story Prize, Tobias Carroll, author of Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms), talks about trying to make use of an admired and complex story structure.

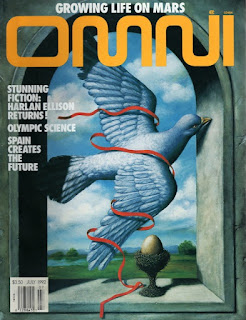

When I was young, I subscribed to OMNI magazine mostly for the science fiction stories that accompanied articles about technology and the future in each issue. And while I don’t remember every story that I read in my high school years, a few have stayed seared into my mind: Ted Chiang’s “Tower of Babylon,” with its reimagining of a familiar story in an entirely fresh form; Jonathan Lethem’s “The Happy Man,” for its jarring blend of a surreal cosmology and quotidian realism; and Harlan Ellison’s “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” for a number of reasons related to both its structure and the narrative that slowly unfolds.

What struck me about it then, and still does, is the way in which it establishes a very rigid structure, and then thoroughly dynamites it. Several stories are nestled within this story. Each paragraph begins with a sentence with the same structure: “On [day of the week] the [date] of [month].” In each, the protagonist, a man known as Levendis, carries out a particular action—some of them innocuous, some heroic, some horrific. It quickly establishes Levendis as someone with miraculous abilities: he can easily traverse time and space, and each day’s events are unique: a story within the stories that make up the larger story.

What struck me about it then, and still does, is the way in which it establishes a very rigid structure, and then thoroughly dynamites it. Several stories are nestled within this story. Each paragraph begins with a sentence with the same structure: “On [day of the week] the [date] of [month].” In each, the protagonist, a man known as Levendis, carries out a particular action—some of them innocuous, some heroic, some horrific. It quickly establishes Levendis as someone with miraculous abilities: he can easily traverse time and space, and each day’s events are unique: a story within the stories that make up the larger story.

By the end of “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” Ellison defies the structure he established earlier, however. It begins with events taking place on the first of October; given its structure, one might expect the story to end on the 31st. It does not; it goes beyond that, treating the framework as one more boundary to transcend—all of which makes for a neat evocation of Levandis’ own ability to leap around the corridors of space and time, as well as an echo of the playful way in which he does so. It’s a hypnotic feat: Ellison established a particular rhythm, and then dismantled it, propelling the reader into the full-on unknown along the way.

***

Clearly, I wanted to try my hand at something that took a similar approach. So far, I haven’t been able to accomplish this. I have a story in progress that would follow a character as they carried out a series of tasks at the rest areas on the Garden State Parkway–partially because, as someone who grew up in New Jersey, rest areas are inexorably wrapped up in my memories of long car trips, and partially because, as spaces go, they fascinate me.

But I haven’t quite found the right way to pull this off yet. There’s a confidence and bravado in Ellison’s story that makes the risks in his structure pay off. And there’s the fact that he uses the repetitive aspects of his structure to counterbalance the more sprawling aspects of it. A narrative that covered similar ground—which could literally be set in an infinite number of locations and an infinite number of points in time—is ultimately given a kind of unity through this device. Remove that scaffolding and the disparate elements might become discordant. Leave it in and there’s a sense of comfort: the reader’s anticipation of what Levandis might do on the next day, and on the day after that.

What makes Ellison’s story work so well is its juxtaposition of rigidity and playfulness—which eventually folds back in on itself as it reaches its conclusion. It’s a work of fiction from which I’m still drawing lessons, and one to which I hope to eventually find the right way to pay homage. “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore” is a fascinating story to revisit and study, though its balance of formality and irreverence seems unique. Still, it’s a short story that contains worlds within it, and closes with a gleeful wink. It’s hard to avoid being impressed, and I’ll most likely be chasing aspects of its structure for years to come.

When I was young, I subscribed to OMNI magazine mostly for the science fiction stories that accompanied articles about technology and the future in each issue. And while I don’t remember every story that I read in my high school years, a few have stayed seared into my mind: Ted Chiang’s “Tower of Babylon,” with its reimagining of a familiar story in an entirely fresh form; Jonathan Lethem’s “The Happy Man,” for its jarring blend of a surreal cosmology and quotidian realism; and Harlan Ellison’s “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” for a number of reasons related to both its structure and the narrative that slowly unfolds.

What struck me about it then, and still does, is the way in which it establishes a very rigid structure, and then thoroughly dynamites it. Several stories are nestled within this story. Each paragraph begins with a sentence with the same structure: “On [day of the week] the [date] of [month].” In each, the protagonist, a man known as Levendis, carries out a particular action—some of them innocuous, some heroic, some horrific. It quickly establishes Levendis as someone with miraculous abilities: he can easily traverse time and space, and each day’s events are unique: a story within the stories that make up the larger story.

What struck me about it then, and still does, is the way in which it establishes a very rigid structure, and then thoroughly dynamites it. Several stories are nestled within this story. Each paragraph begins with a sentence with the same structure: “On [day of the week] the [date] of [month].” In each, the protagonist, a man known as Levendis, carries out a particular action—some of them innocuous, some heroic, some horrific. It quickly establishes Levendis as someone with miraculous abilities: he can easily traverse time and space, and each day’s events are unique: a story within the stories that make up the larger story.By the end of “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore,” Ellison defies the structure he established earlier, however. It begins with events taking place on the first of October; given its structure, one might expect the story to end on the 31st. It does not; it goes beyond that, treating the framework as one more boundary to transcend—all of which makes for a neat evocation of Levandis’ own ability to leap around the corridors of space and time, as well as an echo of the playful way in which he does so. It’s a hypnotic feat: Ellison established a particular rhythm, and then dismantled it, propelling the reader into the full-on unknown along the way.

***

Clearly, I wanted to try my hand at something that took a similar approach. So far, I haven’t been able to accomplish this. I have a story in progress that would follow a character as they carried out a series of tasks at the rest areas on the Garden State Parkway–partially because, as someone who grew up in New Jersey, rest areas are inexorably wrapped up in my memories of long car trips, and partially because, as spaces go, they fascinate me.

But I haven’t quite found the right way to pull this off yet. There’s a confidence and bravado in Ellison’s story that makes the risks in his structure pay off. And there’s the fact that he uses the repetitive aspects of his structure to counterbalance the more sprawling aspects of it. A narrative that covered similar ground—which could literally be set in an infinite number of locations and an infinite number of points in time—is ultimately given a kind of unity through this device. Remove that scaffolding and the disparate elements might become discordant. Leave it in and there’s a sense of comfort: the reader’s anticipation of what Levandis might do on the next day, and on the day after that.

What makes Ellison’s story work so well is its juxtaposition of rigidity and playfulness—which eventually folds back in on itself as it reaches its conclusion. It’s a work of fiction from which I’m still drawing lessons, and one to which I hope to eventually find the right way to pay homage. “The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore” is a fascinating story to revisit and study, though its balance of formality and irreverence seems unique. Still, it’s a short story that contains worlds within it, and closes with a gleeful wink. It’s hard to avoid being impressed, and I’ll most likely be chasing aspects of its structure for years to come.