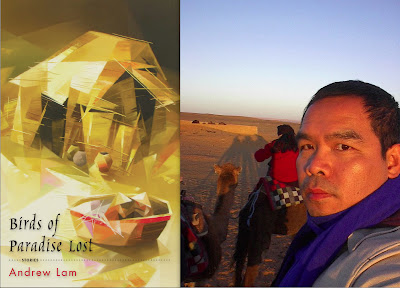

In the 18th in a series of posts on 2013 books entered for The Story Prize, Andrew Lam, author of Birds of Paradise Lost (Red Hen Press), writes of learning to speak English after coming to America from Vietnam as a child.

For a while I was his echo. "Sailboat," he would say while holding the card up in front of me, and "sailboat" I would repeat after him, copying his inflection and facial gestures. "Hospital," he would say. And "hospital," I would yell back, a little parrot.

For a while I was his echo. "Sailboat," he would say while holding the card up in front of me, and "sailboat" I would repeat after him, copying his inflection and facial gestures. "Hospital," he would say. And "hospital," I would yell back, a little parrot.

Then I looked up and saw, far in the distance, San Francisco's downtown, its glittering high rises resembling a fairy-tale castle made of diamonds, with the shimmering sea dotted with sailboats as backdrop.

For years, on my writing desk sat a framed little card, yellow with age, and it told of my American beginning. It's a picture of a sloop, and under it the word "Sailboat" is written, Mr. Kaeselau, my first teacher in America, gave it to me along with a deck of similar cards many decades ago when I was in seventh grade, and fresh from Vietnam.

The only English I knew back home was "no money, no honey," and "Ok, Salem." I learned it from the loud Saigon prostitutes who walked the tamarind tree-lined boulevards near the Independence Palace—across from which stood my school where I was taught Vietnamese and French.

Back then I thought English was a rather terse and ugly-sounding language—you don't have to say much to get your points across, but speak it too long and you risk hurting your throat. In America that fear became true. A few months after having arrived to San Francisco, my voice started to break. The youngest in my family, I went from a sweet sounding child speaking Vietnamese to a craggy sounding teenager speaking broken English. "You sound like a hungry duck," my older brother would say every time I opened my mouth, and everyone laughed.

But not Mr. Kaeselau, who took me bowling with some other students and sometimes drove me home. He had a kind face and a thick mustache that was quite expressive, especially when he smiled and wiggled his eyebrows up and down like Groucho Marx. He gave me A's (which didn't count) before I could put a complete sentence together, "to encourage me," as he would say. At lunchtime, I was one of a handful of privileged kids who were allowed to eat in his classroom and play games—peed, monopoly—and read comic books or do homework. It was a delightful sanctuary for the small kids and the "nerds," who would sometimes get jumped by the schoolyard bullies.

For a while I was his echo. "Sailboat," he would say while holding the card up in front of me, and "sailboat" I would repeat after him, copying his inflection and facial gestures. "Hospital," he would say. And "hospital," I would yell back, a little parrot.

For a while I was his echo. "Sailboat," he would say while holding the card up in front of me, and "sailboat" I would repeat after him, copying his inflection and facial gestures. "Hospital," he would say. And "hospital," I would yell back, a little parrot.

Within a few months, I began to speak English freely, though haltingly, and outgrew the cards. I began to banter and joke with my new friends. I acquired a new personality, a sunny, sharp-tongued kid, and often Mr. Kaesleau would shake his head in wonder at the transformation.

How could he have known that I was desperately in love with my new tongue?

I embraced it like an asphyxiated person in a dark cellar who finally managed to unlock an escape hatch. At home, in the crowded refugee apartment my family shared with my aunt's family, we were a miserable bunch. We wore donated clothes, bought groceries with food stamps, and our ratty sofa with its matching loveseat came from a nearby thrift shop.

I remember the smell of fish sauce wafting in the air and adults' voicees reminiscing of what's gone and lost. Vietnamese was spoken there, often only in whispers and occasionally in exploded exchanges when the crowded conditions became too much to bear. Vietnam ruled that apartment. It ruled in the form of two grandmothers praying in their separate corners. It ruled in the form of the muffled cries of my mother late at night. It ruled in the drunken shouts of an aunt whose husband up and left her and their four children.

In that house, overwhelmed by sadness and confusion, I fell silent. When my father, who had escaped Vietnam a few days after us, managed to finally join us in San Francisco a few months later, things improved. Within two years we even took our first vacation to Lake Tahoe and Disneyland and in another, we moved to our first house in America, our humble American dream.

But by then I had practically stopped speaking Vietnamese all together, becoming as mother said, "A little American." It could not be helped. There was something in English that was in stark contrast with Vietnamese. The American "I" stands alone where the Vietnamese "I" is always a familial limitation, the speaker is bound by his ranking and relations to the listener. In Vietnamese there is very little use for impersonal pronouns. One is son, daughter, father, uncle and so on, and it is understood only in communal and familial contexts, whereas the American "I"—as in I think, I feel, I know, I disagree—encourages personal expression.

It would take me a long, long time before I would embrace my Vietnamese again, balancing the American "I" with the Vietnamese "we," but that, as they say, is another story.

In our refugee home, speaking English was a no-no even if speaking English had already for me becoming second nature. And sometimes, at dinnertime, I would spontaneously sing out a TV jingle with my craggy voice: "My baloney has a first name. It's O-S-C-A-R. My baloney has a second name..." The entire family would look at me as if I were a being possessed. Needless to say, my parents constantly scolded me.

Then one day my brother said with a serious voice. "Mom and Dad told you not to speak English all the time, and you didn't listen, now look what happened. You shattered your vocal cord. That is why you sound like a duck."

Since no one bothered to tell me about the birds and the bees, I fully believed him. I was duped for what seemed like a long time. But I remember being of two minds: While I mourned the loss of my homeland, I, at the same time, marveled at how speaking a new language could actually change me. After all, I was at an age where magic and reality still shared a porous border, and speaking English was to me like chanting magical incantations. It was indeed reshaping me from inside out. I was enchanted by the English language, its power of transformation, and that enchantment, I am happy to report, has never gone away.

When I graduated from junior high, I came to say goodbye to Mr. Kaeslau and he gave me the cards to take home as mementos, knowing full well that I didn't need them anymore. That day, a short day, I remember taking a shortcut over a hill and on the way down, I tripped and fell. The cards flew out of my hand to scatter like a flock of playful butterflies on the verdant slope. Though I skinned my knee, I laughed. Then, as I scampered to retrieve the cards, I found myself yelling out ecstatically the name of the image on each one of them—"School," "Cloud," "Bridge," "House," "Dog," "Car"—as if for the first time.

Then I looked up and saw, far in the distance, San Francisco's downtown, its glittering high rises resembling a fairy-tale castle made of diamonds, with the shimmering sea dotted with sailboats as backdrop.

"City," I said, "my beautiful city." And the words rang true; they slipped into my bloodstream and suddenly I was overwhelmed by an intense hunger. I wanted to swallow the beatific landscape before me. For it was then that I intuited that, through my love for the new language, and through the act of describing and the naming of things, I, too, sounding like a hungry duck, could stake my claims in the New World.