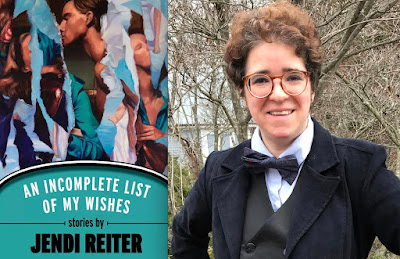

In the 30th in a series of posts from authors of 2018 books entered for The Story Prize, Jendi Reiter, author of An Incomplete List of My Wishes (Sunshot Press), discusses the powerful influence writing can have on a writer.

In the Tarot, the Tower card signifies a disruptive, fundamental change. Richly robed figures tumble headlong from a crown-topped edifice struck by lightning, as droplets of fire rain from a black sky. Yet the building stands on a sturdy rock that has likely weathered many of nature's assaults.

Conventional Tarot readers may dread this card, wanting to give clients good news. But it's one of my favorites. I even have it on a T-shirt.

Writing is hard because our deepest intuition is a force as disruptive—and vital—as the lightning that cracks the Tower wide open. Some cherished beliefs or relationships may not survive the personal growth and truth-telling that the creative process brings forth. Fear of such changes is often the real reason for writer's block, for me and other writers I've known.

Difficulties balancing "writing" and "life" aren't always financial or time-management problems, or even codependence. There's a deeper layer that writing-advice books don't usually acknowledge. We may be correctly perceiving the risk that our work will take us places that our family, friends, community, or religion doesn't want us to go.

Case in point: When I began writing fiction in my early 30s, I thought I was a Christian woman, and now I'm neither. The narrator of my first novel, Two Natures (Saddle Road Press, 2016), simply took over another project and insisted that I tell his story, which somehow felt like my own, despite the superficial differences in our backgrounds. Writing in the voice of a sexually adventurous gay fashion photographer made me realize I'm transmasculine/nonbinary—an option I didn't even know existed till my novel research brought me into a diverse and welcoming queer community.

What does this mean for my happy marriage to a straight man? We're still figuring it out, but it does slow down the process of writing the sequel...and I have to be kind to myself about that. You're not always a "better person" for choosing to preserve relationships—a truth that feels transgressive for writers socialized as female. On the flip side, don't doubt your commitment to the writing, just because you're being careful about its real-life impact.

"Problems with your novel are really problems with your soul," my first fiction-writing mentor, a virtuoso of the literary short story, used to tell me. As an evangelical, she meant that I was blocked and depressed about Two Natures because "sodomy dishonors God." I'll always be grateful for her encouragement of my writing as a spiritual vocation—and I'm still unraveling my shame, fear, and anger from the abusive theology of the community where I first felt the Spirit move. No wonder the book took eight years to finish!

The card that precedes the Tower is the Devil: a giant hairy goat-headed fellow who holds a nude man and woman in bondage with chains round their necks. But interpreters often note that the shackles are loose enough to escape if the human figures weren't so passive. I've learned to welcome writer's block as a sign that some situation in real life is entangling me in chains of my own making, and I'd better break them before the unsustainable structure comes crashing down. In that sense, my Christian mentor's advice is still golden.

Re-committing to my writing flushes out relationships where I'm being gaslighted—made to feel unclear about my perceptions, ashamed of my emotions, obligated to ignore my gut instincts, or forbidden to set boundaries. When I'm in a toxic relationship, I become afraid of my own mind, which arrests the journey into the creative unconscious.

Jesus reportedly said, "If your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to go into hell." (Matt 5:30) This unsettling text has been weaponized against queer people, as a command to cut off a vital part of ourselves—our embodied identities, our capacities for love and pleasure. As with the Tower card, though, I've found the good news within the disruptive shock. It's a promise that I can survive without an attachment I once thought essential—if the alternative is that I'm slowly dying within it.

After the Tower comes the Star, the card of inspiration. An angelic woman, nude and unashamed, pouring the infinite water of life into a pastoral pool. On the other side of writer's block, when outworn supports have crumbled, lies not isolation but a clearer and stronger empathy for myself, my characters, and the world into which I release them.

In the Tarot, the Tower card signifies a disruptive, fundamental change. Richly robed figures tumble headlong from a crown-topped edifice struck by lightning, as droplets of fire rain from a black sky. Yet the building stands on a sturdy rock that has likely weathered many of nature's assaults.

Conventional Tarot readers may dread this card, wanting to give clients good news. But it's one of my favorites. I even have it on a T-shirt.

Writing is hard because our deepest intuition is a force as disruptive—and vital—as the lightning that cracks the Tower wide open. Some cherished beliefs or relationships may not survive the personal growth and truth-telling that the creative process brings forth. Fear of such changes is often the real reason for writer's block, for me and other writers I've known.

Difficulties balancing "writing" and "life" aren't always financial or time-management problems, or even codependence. There's a deeper layer that writing-advice books don't usually acknowledge. We may be correctly perceiving the risk that our work will take us places that our family, friends, community, or religion doesn't want us to go.

Case in point: When I began writing fiction in my early 30s, I thought I was a Christian woman, and now I'm neither. The narrator of my first novel, Two Natures (Saddle Road Press, 2016), simply took over another project and insisted that I tell his story, which somehow felt like my own, despite the superficial differences in our backgrounds. Writing in the voice of a sexually adventurous gay fashion photographer made me realize I'm transmasculine/nonbinary—an option I didn't even know existed till my novel research brought me into a diverse and welcoming queer community.

What does this mean for my happy marriage to a straight man? We're still figuring it out, but it does slow down the process of writing the sequel...and I have to be kind to myself about that. You're not always a "better person" for choosing to preserve relationships—a truth that feels transgressive for writers socialized as female. On the flip side, don't doubt your commitment to the writing, just because you're being careful about its real-life impact.

"Problems with your novel are really problems with your soul," my first fiction-writing mentor, a virtuoso of the literary short story, used to tell me. As an evangelical, she meant that I was blocked and depressed about Two Natures because "sodomy dishonors God." I'll always be grateful for her encouragement of my writing as a spiritual vocation—and I'm still unraveling my shame, fear, and anger from the abusive theology of the community where I first felt the Spirit move. No wonder the book took eight years to finish!

The card that precedes the Tower is the Devil: a giant hairy goat-headed fellow who holds a nude man and woman in bondage with chains round their necks. But interpreters often note that the shackles are loose enough to escape if the human figures weren't so passive. I've learned to welcome writer's block as a sign that some situation in real life is entangling me in chains of my own making, and I'd better break them before the unsustainable structure comes crashing down. In that sense, my Christian mentor's advice is still golden.

Re-committing to my writing flushes out relationships where I'm being gaslighted—made to feel unclear about my perceptions, ashamed of my emotions, obligated to ignore my gut instincts, or forbidden to set boundaries. When I'm in a toxic relationship, I become afraid of my own mind, which arrests the journey into the creative unconscious.

Jesus reportedly said, "If your right hand causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away. It is better for you to lose one part of your body than for your whole body to go into hell." (Matt 5:30) This unsettling text has been weaponized against queer people, as a command to cut off a vital part of ourselves—our embodied identities, our capacities for love and pleasure. As with the Tower card, though, I've found the good news within the disruptive shock. It's a promise that I can survive without an attachment I once thought essential—if the alternative is that I'm slowly dying within it.

After the Tower comes the Star, the card of inspiration. An angelic woman, nude and unashamed, pouring the infinite water of life into a pastoral pool. On the other side of writer's block, when outworn supports have crumbled, lies not isolation but a clearer and stronger empathy for myself, my characters, and the world into which I release them.