|

| Hit Leaders: Broughman and Blakeslee |

It's been fun while it lasted, but because of steady declines in both author participation and the audience for these blog posts, 2018 will be the final year of this series. In its place, we hope to offer an opportunity for authors whose books we read in 2019 to contribute an image that relates to their collection, along with a short paragraph or two about the image, that we'll post on The Story Prize Instagram account.

According to Blogger's statistics, most 2018 author guest posts received 250 or more page views, down from an average of 400 last year. The most popular post, Chad V. Broughman on Being a Writer and a Parent, has so far drawn nearly 2,000 page views. Last year's leader, Karen Shepard: How to Make Intermittent and Erratic Progress as a Writer, in Twenty-Eight Easy Steps, had more than 4,500 page views—the sixth most of any TSP blog post, at the time (It is now the fourth most popular post, with almost 7,000 page views). Antonya Nelson's Ten Writing Rules, the post with the most all-time views, currently has well over 14,000 page views.

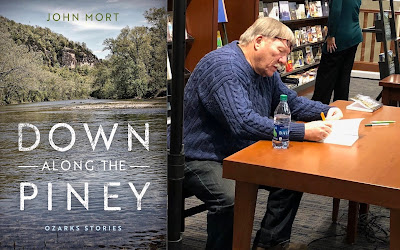

The 2018 author contribution with the second most hits was Vanessa Blakeslee's Eight Most Anticipated 2018 Story Collections, with close to 1,000 page views to date. The two posts with the largest Facebook reach were Chad V. Broughman's and John Mort on Writing Short Stories and Raising Vegetables.

Here's the index for 2018.

A-B

Camille Acker on an Individualistic Writing Process

Jacob M. Appel's Misguided Advice

Where Do Stories Come from? Ramona Ausubel's Visual Guide

Matthew Baker's Experiments with Language

Karen E. Bender's Advice to a Young Writer: Thoughts on the Structures That Hold up the House of the Story

Thomas Benz: In Defense of Elaboration

Chaya Bhuvaneswar on Writing Under Difficult Conditions

Vanessa Blakeslee's Eight Most Anticipated 2018 Story Collections

Lucy Jane Bledsoe on How Not to Outline a Short Story

Chad V. Broughman on Being a Writer and a Parent

Jacob M. Appel's Misguided Advice

Where Do Stories Come from? Ramona Ausubel's Visual Guide

Matthew Baker's Experiments with Language

Karen E. Bender's Advice to a Young Writer: Thoughts on the Structures That Hold up the House of the Story

Thomas Benz: In Defense of Elaboration

Chaya Bhuvaneswar on Writing Under Difficult Conditions

Vanessa Blakeslee's Eight Most Anticipated 2018 Story Collections

Lucy Jane Bledsoe on How Not to Outline a Short Story

Chad V. Broughman on Being a Writer and a Parent

D-K

Jane Delury Asks: Are We There Yet?Peter Donahue Untrues Sentences

Sherrie Flick on Organizing a Book Tour

Elena Georgiou's Letter to a Not-So-Young Writer

Nancy Gerber on Naming Characters

Ryan Habermeyer on (Re)Upholstering a Story

Adrianne Harun's Nine-Part Writing Advice

Ruth Joffre’s Reading Habits

Why Audrey Kalman Reads Mary Oliver in the Morning

Sherrie Flick on Organizing a Book Tour

Elena Georgiou's Letter to a Not-So-Young Writer

Nancy Gerber on Naming Characters

Ryan Habermeyer on (Re)Upholstering a Story

Adrianne Harun's Nine-Part Writing Advice

Ruth Joffre’s Reading Habits

Why Audrey Kalman Reads Mary Oliver in the Morning

L-O

P-S

U-X

Kimberly Lojewski Writes A Letter to Her Young Self: On the Dangers of Magic Portals, Nyquil, and Renaissance Faire Carnies

Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum on Stargazing and Writing Short Fiction

All Wendell Mayo's Lonely Ones

K.D. Miller Shows Up

Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum on Stargazing and Writing Short Fiction

All Wendell Mayo's Lonely Ones

K.D. Miller Shows Up

John Mort on Writing Short Stories and Raising Vegetables

Scott Nadelson and the Quest for the Right Voice

Scott O'Connor on Embracing Uncertainty

Scott Nadelson and the Quest for the Right Voice

Scott O'Connor on Embracing Uncertainty

Victoria Patterson's Letter to Her Beginning Writer Self

Todd Robert Petersen's Pyramid Problems

Niles Reddick on the Business Side of Writing

Todd Robert Petersen's Pyramid Problems

Niles Reddick on the Business Side of Writing

Jendi Reiter on Choosing Relationships That Support Their Writing

Anjali Sachdeva: In Praise of Old Stories

Two Books That Speak to Jen Silverman

Curtis Sittenfeld's Breakthrough Experience

Nancy Stohlman on the Biggest Mistake Writers Make

Anjali Sachdeva: In Praise of Old Stories

Two Books That Speak to Jen Silverman

Curtis Sittenfeld's Breakthrough Experience

Nancy Stohlman on the Biggest Mistake Writers Make