Which story in your collection required the most drafts or posed the most technical problems?

In My Date with Neanderthal Woman, the story that caused me the biggest headache was “The Adjuster,” a long, over-eloquent narrative about an academic type, Berger Bergson, whose mission is to question the easy wisdom of aphorisms (see what I mean?). Unable to go beyond the premise and a few establishing scenes, I put down the story for three years and finally finished it when I realized where Bergson’s career would take him. I felt as if I had to invent everything for him, not just co-opt details from lives I knew.

If you’ve substantially reworked any of the stories that originally appeared in magazines, can you explain what you changed and why?

The one most worked over was “All You Can Eat,” originally titled “Buffet.” The editor at Bull: Fiction for Men liked the piece, which was all of three pages, but made a number of improving suggestions. I followed them up, only to receive more comments, and because I valued the editorial feedback I was getting, I gamely addressed them all. This process occurred about five times. In the end, the whole storyline altered, including “in the end,” where the main character has a sort of nagging non-epiphany.

What is your writing process like?

What with teaching, administering a creative writing program, and trying to be a good family member, I see my writing process these days as “Prepare some notes ahead of time, then grab whatever time you can at the keyboard. Repeat as necessary.”

How did you decide to arrange the stories in your collection?

Because this collection is a mixture of conventional-length stories and a lot of short-shorts, the trick was to avoid both the short-long-short pattern, like unsuccessful Morse code; and also sequences of shorts, like beads on a string. Finally, I had to think thematically: what would best riff off what.

At what stage do you start seeking feedback on your work and from whom?

If you dabble in any other non-literary forms of expression, what do you do and how does it inform your work?

At what stage do you start seeking feedback on your work and from whom?

I show my work to a few friends and try not to abuse the privilege. My wife, who’s a journalist and magazine editor, is excellent at telling me when something feels dated or just lacks a hook.

What do you think a good short story collection should deliver?

What do you think a good short story collection should deliver?

Seventeen different stories: seventeen different worlds. Otherwise, might as well read a novel.

What book or books made you want to become a writer?

What book or books made you want to become a writer?

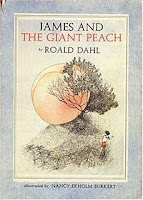

I read all over the place when I was growing up, and still do, but the books I most admired then were those with really fine “what if?” premises, anything from Roald Dahl to P. G. Wodehouse, or fantasy and science fiction by authors like Robert Heinlein or Ray Bradbury.

What kind of research, if any, do you do?

What kind of research, if any, do you do?

I check facts as necessary, especially if I position a character in an air conditioning plant or have her working as a bartender, since I’ve never held down either of those jobs. And though I don’t love research the way some authors seem to, I try to go onsite, because you never know what’s going to turn up: the unsuccessfully disinfected odor from the soup kitchen, or the stack of business folders shoring up a flower pot in someone’s office.

If you dabble in any other non-literary forms of expression, what do you do and how does it inform your work?

Well, I publish all over the map and call myself a shameless eclectic, but I’d be hard put to distinguish between my literary and non-literary endeavors. I do translation, poetry, literary criticism, and humor columns alongside my fiction and don’t think about whether they’re literary. It all just cross-pollinates my work.

Have you ever written a short story in one sitting and not revised it later?

Have you ever written a short story in one sitting and not revised it later?

Yes, though that happens less and less as I grow older. Still, the title story of this collection, “My Date with Neanderthal Woman,” was written in one go and left virtually intact. The usual irony: it’s the one that’s had the most success, from publication in a Norton anthology to Spanish translation and being performed by a professional actor in Los Angeles.

Have you had a mentor, and who was it?

Have you had a mentor, and who was it?

Alas, no. Teachers, yes, including Joyce Carol Oates, Ivan Gold, and Stephen Koch. Maybe I’m just not the mentee type.

What’s the longest narrative time period you’ve ever contained in a short story?

What’s the longest narrative time period you’ve ever contained in a short story?

A lifetime, cradle to grave, though my character died young, at the age of 43. At the time, I thought that was fairly old.