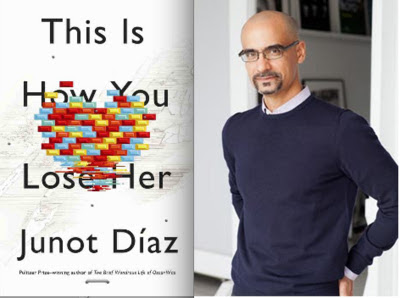

In the 45th in a series of posts on 2012 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, Junot Diaz, author of This Is How You Lose Her (Riverhead Books), speaks about what isn't there.

I've always been interested in how you write silences. How do you include or mark in a piece of fiction what isn’t said between the characters, the narrative that is missing even from the characters’ perceptions of the world. How do you as a storyteller account for traces of the erased, the denied or that flat out vanished? These are concerns that sit with me always when I write stories. I often begin my stories by first sketching their primal silence and then elaborating the story around that silence. Sometimes what's missing is pretty obvious to the reader: a character or a place that’s disappeared and that the characters do not wish to confront. But other times it’s far more cryptic, a silence that I keep to myself but whose resonances power the prose, work like a dark energy on the matter of the prose.

In my novel Oscar Wao the silences are many and intentionally so. The book is organized around various unrecoverable absences. One of the most obvious is of course Oscar de León himself. Some readers might not notice that for all of Oscar’s “presence” in the book he is never actually present. We always receive him through the mediation of the narrator, Yunior. We never hear directly from him, which is odd, no, consdering that he is a writer after all. All of Yunior’s narrative muscles hide the fact that Oscar is not there at all. And when one discovers that one should always ask: why?

In my novel Oscar Wao the silences are many and intentionally so. The book is organized around various unrecoverable absences. One of the most obvious is of course Oscar de León himself. Some readers might not notice that for all of Oscar’s “presence” in the book he is never actually present. We always receive him through the mediation of the narrator, Yunior. We never hear directly from him, which is odd, no, consdering that he is a writer after all. All of Yunior’s narrative muscles hide the fact that Oscar is not there at all. And when one discovers that one should always ask: why?

|

| © Nina Subin |

Haruki Murakami’s novels are rich with silences. So are the early Morrison books. And of course Cormac McCarthy leaves out a whole lot more than he puts in. (See Blood Meridian for a masterwork in lacuna studies.) If you haven’t read Terrence Holt’s In the Valley of the Kings please rush to do so. Another great master of elision; the collection's title story is a seminar on narrative gaps. Rushdie on the other hand is one of my favorite writers in the world, but he’s not all that awesome at silences. Or if he is I haven’t noticed; my failure.

In my novel Oscar Wao the silences are many and intentionally so. The book is organized around various unrecoverable absences. One of the most obvious is of course Oscar de León himself. Some readers might not notice that for all of Oscar’s “presence” in the book he is never actually present. We always receive him through the mediation of the narrator, Yunior. We never hear directly from him, which is odd, no, consdering that he is a writer after all. All of Yunior’s narrative muscles hide the fact that Oscar is not there at all. And when one discovers that one should always ask: why?

In my novel Oscar Wao the silences are many and intentionally so. The book is organized around various unrecoverable absences. One of the most obvious is of course Oscar de León himself. Some readers might not notice that for all of Oscar’s “presence” in the book he is never actually present. We always receive him through the mediation of the narrator, Yunior. We never hear directly from him, which is odd, no, consdering that he is a writer after all. All of Yunior’s narrative muscles hide the fact that Oscar is not there at all. And when one discovers that one should always ask: why?

Then there’s the silence at the heart of Yunior’s character—he is the protagonist of sorts of all three of my books—a silence which defines so much of what he is and what he bears witness to and why he connects with the women and people that he connects with. A silence he has yet to confront.

We live in a culture whose expression baseline is the over-confessional mode. The compulsive over-confessional mode. We’ve all gotten so damn loud and you don’t need David Foster Wallace to tell you that. At times it feels like too much information is no longer an exception but the order of the day. One of my favorite stories in the world is an Octavia Butler tale where the narrator suffers from a malady that in its final stages compels its victims to tear themselves apart; when the disease takes over they start digging into their flesh with their own fingers, tearing themselves open as if to get at something. When I think of how compulsive many people in our culture are with their over-sharing, that story is never far. At a cultural level we’re that story’s children, suffer the same malady, tearing ourselves open for others' delectation or just because we’ve been told that’s the best way to get attention. I’m sure there are plenty of other reasons, but in such a climate silence for many people is not even a possible strategy; for me it is the substance out of which I carve my narratives. I often fragment my books because in the game of articulating the narrative pieces a reader can begin to suss out through that deliberative process what is missing; they begin to slowly form a picture of the book’s absences. This for me is one of my secret joys: I read for the silences. Or to put it more ridiculously: I may come for the story but I stay for the silences.