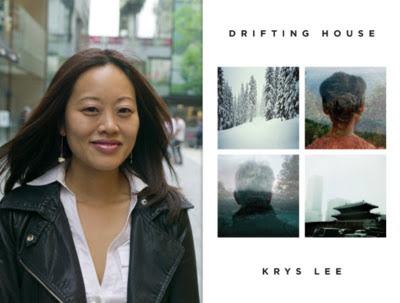

In the 69th in a series of posts on 2012 short story collections entered for The Story Prize, Krys Lee, author of Drifitng House (Viking), discusses what motivates and inspires her.

What made you want to become a writer?

What made you want to become a writer?

Reading saved my life when I was young, and unfortunately, I’m not exaggerating. The next step, moving from reading to writing, came naturally, as I grew up loving the escape into stories and words. Discovering a world—and word—I didn’t know, was a thrill, and to put words down on paper showed me that there was so much rage, hurt, and love I hadn’t been able to express. Writing allowed me to release that secret self that was uglier, harder, as well as more hopeful and more willing to dream, than my public self. I wanted to write and create a world that wasn’t about me, but by writing, I found myself looking back at me from the pages. Today, I write for those reasons, and more. When I can’t change or fix what I find unjust in the world, or see the secret selves of misunderstood or neglected others, I find myself wanting to write.

Where do you find inspiration?

The world and its people are my inspiration. I’ve lived on three continents and have spent exactly half my life speaking in two different languages. I grew up in the United States without knowing what it meant to have health insurance and saw my parents lose the very little that they had before I was twenty-one, and now live a stable life with more opportunities than my parents. My good friends range from professors, park rangers, writers and readers, to North Korean defectors. This navigation between worlds has liberated me from a fixed sense of what is real, what is right, and who I (or anyone) is. This constant relativity can be a bit dizzying, and sometimes a little lonely, but I try to understand the rich chaos of the world is through fiction.

The world and its people are my inspiration. I’ve lived on three continents and have spent exactly half my life speaking in two different languages. I grew up in the United States without knowing what it meant to have health insurance and saw my parents lose the very little that they had before I was twenty-one, and now live a stable life with more opportunities than my parents. My good friends range from professors, park rangers, writers and readers, to North Korean defectors. This navigation between worlds has liberated me from a fixed sense of what is real, what is right, and who I (or anyone) is. This constant relativity can be a bit dizzying, and sometimes a little lonely, but I try to understand the rich chaos of the world is through fiction.

Books are also a source of excitement and inspiration. When I read a book that excites me, I feel, as Emily Dickinson put so well, as if the top of my head were taken off. Most recently, I had that experience when I read Jeet Thayil’s incredible novel Narcopolis. I also turn to history, philosophy, poetry. Words, words, words. They excite me.

What obstacles have you encountered in your work, and what have you done to overcome them?

I’m my greatest obstacle. When I first began writing, it was my lack of confidence and feeling that nothing I wrote would ever be worth reading. Later, it was my lack of concentration. I’m a restless person, have never been great at sitting down for extended periods of time unless I’m reading, and I don’t take Adderall or any of those other aids that some writers use to pull them through the writing day. Instead of fighting this, I allow myself to stay involved in other work that I care about, go kayaking when that’s what my body is wanting, read, travel, or wander around different neighborhoods. I began writing for myself as an act of need and pleasure, and I want to respect that first impulse. As long as writing is a steady part of my life, I accept my restlessness, though I wish I had the work habits of Philip Roth.

How often does an idea for a story occur to you, and what triggers those ideas?

When I was working on the stories, new ideas came to me nearly every other day. I saw the world through story, or as story. I jotted down entire introductions to ideas that excited me that I haven’t had time to return to yet. But since I began working on a novel, this has been happening to me far less. In my experience, there’s something about being immersed in the universe of the novel that seems to suppress the impulse toward all the disparate story ideas that might come to a person in a day. Rather, if I get ideas, they are already implicitly a part of the novel or are new novel ideas, all which have a very different feel and shape than my story ideas did. Writing stories allowed me to imagine radically.

Where do you do most of your work?

I write most of the time in the library, cafes, or in bed. I enjoy the library because all the others studying helps writing feel like a slightly less isolating endeavor. The distractions are always entertaining too, as men have occasionally clipped their toes or started rambunctious rows a few feet away from me. These days I’m usually in my favorite book café in Seoul run by a major South Korean publisher. The high ceilings, the presence of books, and the buzz of people talking about and writing create a good working environment. And the incredible hot chocolate doesn’t hurt either. I resort to the bed when I can’t bear the idea of sitting upright and working. Something about staying prostrate while sipping hot chocolate and tapping at the keyboard with two fingers reminds me that writing is also play and pleasure.

But the real answer is that if I don’t feel as if I can write in a certain environment, I’ll write wherever I can, whether it is the subway, in a tent camping, or sitting on a bench in a park. Days off writing and away from the desk are an important part of writing, too.

What writer or writers have you learned the most from?

I’d like to claim everyone from Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Kurt Vonnegut, but in retrospect I think the economy and restraint of Ernest Hemingway and Elizabeth Bishop the poet have been influential. I grew up as a teenager reading the oeuvre of Hemingway and Bishop (a modest collection), and it seems to have influenced my impatience with pretty words that aren’t doing much on the page. Virginia Woolf was also very important to me. Her narrative vision and the tension and energy of her sentences were important to me, as were her life-long obsessions with time and death.

What story by another writer do you most wish you'd written?

There are so many. I admire Anton Chekov’s “The Lady with the Dog” for its understated, heartbreaking power and the way we feel the expanse of the characters’ lives within a moment. Nikolai Gogol’s “The Overcoat” is a story that anyone interested in stories as well as the human condition should read. Also, if I can throw another one in, it would probably be Lorrie Moore’s “Which Is More Than I Can Say About Some People.” It’s a wicked, funny story that turns into one of understanding and even tenderness. I admire humor in fiction precisely because it eludes me. I may start with draft of a comic story but as I revise, it inevitably turns into some dark tale.